by Wandile Sihlobo | Feb 18, 2021 | Food Security

The folks at Newsi.co.za asked me to write an article on South Africa’s food security conditions; and outline risks to the country’s food security, which policymakers, farmers and agribusiness will need to monitor closely.

Climate change, suggestions of widespread expropriation without compensation, increasing rural crime and rising protectionism are critical risks that I believe need closer attention to maintain a food secure country.

You can read the full article by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo).

by Wandile Sihlobo | Feb 17, 2021 | Food Security

South Africa’s food price inflation softened to 5,6% y/y in January 2021, from 6,2% y/y in the previous month. The deceleration was in most product prices in the food basket except for bread and cereals, which accelerated from the levels seen in December 2020. Nevertheless, this was overshadowed by the slowing price inflation in meat; fish; milk, eggs and cheese; fruit; and vegetables.

The “bread and cereals” products price inflation mirrors the increases observed in the past few months in grain prices. The current slightly elevated price inflation for this particular product prices will likely prevail for most of the first quarter as grain prices have continued to surge since the start of the year. While South Africa had its second-largest grains harvest in history in the 2019/20 production season, and ordinarily one would have expected prices to soften, we have experienced the opposite. Grain prices remained elevated on the back of strong demand for South African maize across the Southern Africa region and the Far East markets. The weaker domestic currency also added to the price increase and spillovers from higher global grains prices. The global grains market was primarily driven by the growing demand for grains in China.

Nevertheless, we expect South Africa’s grain prices to soften from the second quarter on the back of an expected sizeable domestic maize harvest of 16,6 million tonnes from 15,4 million tonnes in 2019/20 production season. This is all against South Africa’s annual consumption of about 11,4 million tonnes.

Meat, which has a higher weighting of 35% in the food basket, saw price inflation decelerating in January 2021, in part, due to increased supply following slightly higher slaughtering activity in December 2020. Cattle slaughtering was up by 1% in December 2020, at 281 043 head. This slight increase, combined with relatively depressed household incomes, has partly contributed to softening price inflation for the product. In terms of vegetables and fruit, the domestic supply recovery is mainly the contributing factor to easing price inflation.

From now on, we still expect South Africa’s food price inflation to remain at slightly elevated levels in the first quarter of the year because of higher grain prices and the imported vegetable oils and fats. But from the second quarter of the year, grain prices could soften and filter through, with a lag, on the “bread and cereals” products prices. This product category also has a higher weighting of 21% in the food basket, and changes in its price inflation will be noticeable. In terms of meat, we expect a sideways price movement for the coming months. Slaughtering could slightly improve in 2021 in cattle, and the base effects on poultry meats, which increased in 2020 partly as a result of an import tariff hike, could also bode well for food price inflation.

In sum, we believe South Africa’s food price inflation could remain relatively higher in the first quarter of 2021, primarily underpinned by bread and cereals products (the pass-through of current higher grains prices will persist for the first quarter). But from the second quarter, we could see food price inflation decelerating somewhat. Our baseline view is for food price inflation to average around 5,0% y/y in 2021.

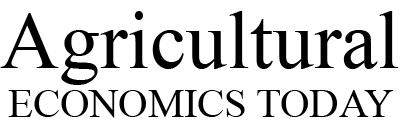

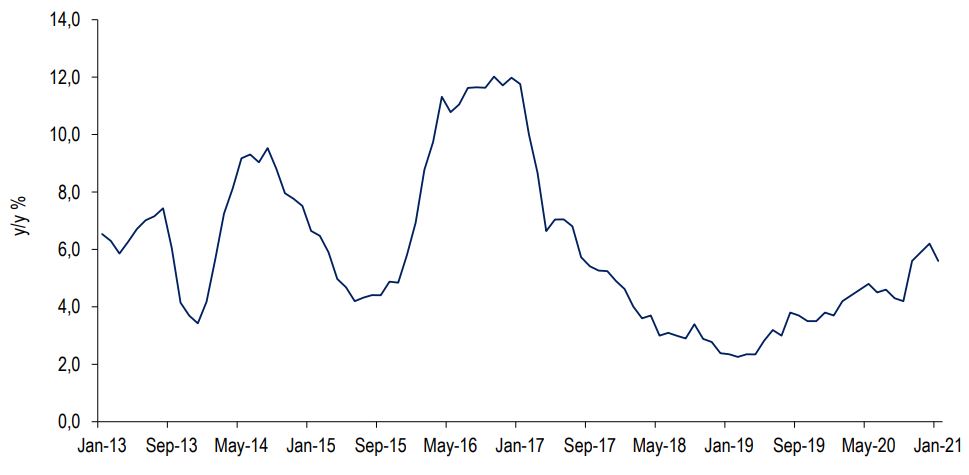

Exhibit 1: SA Food Price Inflation

Source: Stats SA and Agbiz Research

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo).

by Wandile Sihlobo | Feb 12, 2021 | Food Security

South Africans are not the only ones experiencing a relative increase in agricultural commodity prices. The world over is experiencing a similar trend, at least, for essential commodities such as grains, dairy and vegetable oils. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations recently released an update of its monthly Food Price Index, which reached 113 points in January 2021, up 10% year-on-year, and highest since July 2014. This particular index is compiled as a combined index from agricultural commodity prices in various countries, thus mirroring a fair view of relative global food prices.

In South Africa, whether one looks at maize prices or soybeans, wheat or sunflower seed; the price trend shows a notable uptick over the past couple of months; roughly in line with the global trend. For example, on Friday, 05 February 2021, South Africa’s white and yellow maize spot prices closed at R3 299 and R3 451 per tonne, respectively up by 8% and 21% from the corresponding period last year. On the same day, South Africa’s soybeans spot price closed at R9 990 per tonnes, which is 65% higher than the corresponding period last year.

To some, such increases would be counterintuitive in a year where we expect another bumper crop in South Africa, aided by increased summer crop plantings and favourable rains since the start of the 2020/21 production season in October. But because South Africa is a relatively small player in the global agricultural market — particularly grains — market dynamics in major producing and consuming countries influence the domestic price movements. The somewhat weaker domestic currency also contributed to the price increases, amongst other factors.

Staying with grains and oilseeds, which are amongst the aforementioned global Food Price Index’s price drivers, China’s rising demand has been exceptionally fundamental in the current surge of prices.

Click here to read the full column for this week in Fin24.

FAO Global Food Price Index

Source: FAO and Agbiz Research

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo).

by Wandile Sihlobo | Jan 20, 2021 | Food Security

The higher grain prices and a decline in cattle slaughtering activity over the past few months have started to transmit into the prices of products consumers pay when doing their groceries.

In the fourth quarter of 2020, South Africa’s food price inflation was on an upwards trajectory, with the December print accelerating to 6.2% year-on-year (y/y), from 5.9% y/y in the previous month. This is the highest rate since July 2017, when food price inflation was at 6.8% y/y.

South Africa’s food price inflation averaged 4.8% in 2020, up from 3.1% y/y in 2019. These are still relatively comfortable levels compared with the drought-related surge of 2016, where South Africa’s food price inflation averaged 10.8% y/y.

The drivers of the increase in the headline food price inflation in the last quarter of the year were primarily the bread and cereals; meat; fish; milk, eggs and cheese; and oils and fats.

In the case of “bread and cereals” – which consists mainly of essential products and with a weighting of 21% in the food basket — the underpinning driver of acceleration in price inflation is the higher grains prices. While South Africa had its second-largest grains harvest in history in 2019/20 production season, and ordinarily, one would have expected prices to soften, we have in fact experienced the opposite. Grains prices remained elevated on the back of strong demand for South African maize across the rest of the Southern Africa region and the Far East markets. The weaker domestic currency also added to the price increase, along with spillovers from higher global grains prices. The global grains market was primarily driven by the growing demand for grains in China. But most recently, La Nina induced dryness in parts of Argentina and Brazil continues to support prices.

Meat, which is also an essential product in the food basket, with a 35% weighting, saw prices increasing due to various factors. Chief amongst them was the progressive decline in slaughtering numbers towards the end of 2020. In October 2020, sheep and cattle slaughtering was down by 22% y/y and 2% y/y, respectively.

For milk products price, the was also a seasonality factor; whereas the fats and oil prices were, in part, underpinned by the weaker domestic currency. South Africa remains a net importer of vegetable oils.

Now, this is all history, and the critical question is whether this upward swing on food prices could form a prolonged trend for much of this year? I don’t think so.

First, while La Nina causes dryness in South America (with a negative impact on crops), Southern Africa is the opposite. We have been receiving higher-than-usual rainfall which has boosted crop conditions, not only here in South Africa but across the Southern Africa region. This means that there are expectations of a good harvest in Southern Africa.

For South Africa, my preliminary estimates are that we could have a maize harvest of at least 16.0 million tonnes, which would overtake the 2019/20 season’s harvest of 15.4 million tonnes and be the second largest on record (against an annual consumption of 11.4 million tonnes).

Under this scenario, and improved crop harvest across Southern Africa, we could see the demand that existed in 2019/20 crop declining, thus taking some pressure off domestic crop prices. All else being equal, I think South Africa’s grains prices could soften from around end of February this year, from the current highs of over R3 500 per tonne.

On meat, slaughtering could slightly improve this year and the base effects on poultry meats, which increased in 2020 partly as a result of an import tariff hike, could also bode well for food price inflation

However, I am less optimistic about fats; the relatively weaker domestic currency and elevated global vegetable oil could mean that oils and fats price inflation could be slightly elevated for some time.

In terms of fruits and vegetables, the good rains across the country could boost supplies and keep prices broadly steady.

Against this backdrop, I believe that South Africa’s food price inflation could remain elevated in the first quarter of 2021; primarily underpinned by bread and cereals products (the pass-through of current higher grains prices will persist for the first quarter). But from the second quarter, we could see food price inflation decelerating somewhat. My baseline forecast is for food price inflation to average around 5% y/y in 2021.

Source: Stats SA, Agbiz Research

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo).

by Wandile Sihlobo | Jan 6, 2021 | Food Security

While 2020 was generally a good year for most of South Africa’s agricultural sector on the back of large production, a few subsectors were slightly under pressure. The poultry and livestock industries are among such subsectors (including the wine and tobacco industries that were impacted by covid-19 regulations).

The higher maize and soybeans prices towards the end of 2020 led to increasing costs for these industries. For context – roughly 50-70% of broiler production costs in South Africa are attributed to the feed, of which 70–80% comes from maize and soybean costs.

My view has been that the price increase was temporary. From February 2021, South Africa’s maize and soybeans prices could soften substantially on the back of the expected sizeable domestic harvest in 2020/21 season. Such a decline in prices would be positive for the poultry and livestock industries. But I am now beginning to doubt, especially about soybean prices, whose trend is primarily influenced by global events. For maize, I maintain a view that prices could soften in the coming weeks, as I explained here.

The talk of dryness in South America – Argentina and parts of Brazil — and continuous downward revision of the 2020/21 maize and soybean production prospects for both countries has led to a substantial increase globally on maize and soybean prices.

Added to this is an ever-rising demand from China, which is currently rebuilding its pig herd which was devasted by the African swine fever.

Ok, I am speculating here (and not necessarily saying events will unfold this way) — the higher feed costs could subsequently slow South Africa’s efforts on poultry import substitution.

We need affordable feed to boost the local poultry industry, and South Africa is still heavily dependent on soybean oilcake/meal imports to support the local industry.

And yes, the efforts to grow the domestic soybean industry have paid off – see a linked article by clicking here. Still, we have a long way to go before we could be self-sufficient in soybean production. South Africa currently imports nearly half a million tonnes of soybean meal, primarily from Argentina.

So, what to do about all this?

A long-term view is that; increasing maize production in the underutilized lands of the Eastern Cape and Kwa-Zulu-Natal, then substitute yellow maize plantings in Mpumalanga with soybeans would be an avenue to improve South Africa’s animal feed costs and supplies. This line of argument eventually brings us to the point I made a few days ago about the need to drive commercialization of black farmers in South Africa, cultivating the underutilized lands in the former homelands (I’ve discussed at length here).

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo).

by Wandile Sihlobo | Dec 13, 2020 | Food Security

At the start of the year, I highlighted two threats that were imminent at that time in South Africa’s agricultural sector, namely drought and bio-insecurity (specifically foot-and-mouth disease). At that time, it looked as though 2020 would not be much different from 2019, a challenging year in which the sector’s gross value added contracted by almost 7% due to climatic challenges.

Several areas experienced drier than normal conditions, including the Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, North West, Limpopo and parts of the Free State. In terms of biosecurity, the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak reported at the end of 2019 curtailed exports of animal products and wool.

However, by the end of January, the outlook for the sector had turned positive. It had finally rained across the country and crops looked promising, despite most having been planted outside the optimal window.

As the season progressed, with the crops promising to be one of the best in history, Covid-19 concerns intensified in China, and at the start of March, we were bitterly reminded how interconnected the globe has become as we worried about possible disruptions to SA’s exports to the Asia region in such a bountiful year. Not long after that SA began recording its first Covid-19 cases and the country went into hard lockdown towards the end of March.

At this juncture, one of the key questions troubling policymakers and the public was whether SA could be self-sufficient for a long period as countries went into lockdown and consumers were hoarding food products. Fortunately, it quickly became clear that SA’s formal food supply chains were resilient, and they remained functional throughout, with minimal interruptions other than those caused by the regulations themselves.

Credit for the unhindered operation of the food value chain must be shared by the government, private sector and various research institutions. Importantly, the government’s decision to leave the agricultural and broader food sector fully operational from the onset of the lockdown provided conducive business conditions.

It is through these joint efforts that SA’s agricultural gross value added showed a notable expansion at double digits in the first half of the year. Also, the ban on livestock exports was lifted earlier in the year as some regions of the country were cleared of foot-and-mouth disease. This positive picture was, nonetheless, at the aggregate level. The wine and tobacco industries were hard hit by the ban on sales during the various stages of the lockdown.

Large harvests and continuation of the food value chain activities with minimal interruptions also kept food price inflation subdued. In the first 10 months of 2020 SA’s food price inflation averaged 4.5% year on year. This is a notable improvement compared with drought years such as 2016, when food price inflation averaged 10.8%. There were, nonetheless, communities that struggled to get food, but one can argue that such challenges were not primarily caused by rising food prices, rather the lack of buying power as people lost jobs and livelihoods during the lockdown.

In sum, 2020 has been an eventful year, yet with broadly positive results for agriculture — with the exception of the wine and tobacco industries, as previously mentioned. I look to 2021 with hope for yet another strong performance for agriculture, underpinned by a favourable production season, though the growth numbers are unlikely to be double digits in part because of base effects.

Annual food price inflation should also remain contained and probably average no more than 5%, although earlier months of the year could show higher numbers due to elevated grain prices. The pass-through could appear early in 2021 but soon dissipate after the expected large grain harvests in the 2020/2021 season.

This essay first appeared on Business Day, December 8, 2020

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo).

by Wandile Sihlobo | Nov 25, 2020 | Food Security

My intention in this blog post is to briefly discuss South Africa’s food price inflation data for October 2020, which showed a sharp increase to a level last seen in August 2017, as illustrated below in Exhibit 1 below.

Exhibit 1: South Africa’s food price inflation

Source: Stats SA, Agbiz Research

South Africa’s food price inflation accelerated to 5.6% y/y in October 2020 from 4.2% in the previous month, and well above the average of 4.4% for the first nine months of the year. This was broad-based and reflective of the agriculture commodity price increases we have observed in the past few months. I will single out a few, with higher weighting on the food price inflation basket, namely: (1) Bread and cereals, (2) Meat, (3) Vegetables, (4) Milk, eggs and cheese, and (5) Oils and fats.

First, the increases in bread and cereals price inflation mirrors, although to a limited extent, the surge in grains prices that’s been underway over the past couple of months (see Exhibit 2). The South African grains prices were pushed higher mainly by the weaker domestic currency, stronger demand in the Southern Africa region and also the Far East, as well as generally higher global grains prices, which are, in turn, supported by strong demand from China. This happened despite the country having received its second-largest maize harvest in history in 2019/20, about 15.4 million tonnes.

Exhibit 2: Maize (white) prices generally higher in 2020, well above the recent years

Source: JSE, Bloomberg, Agbiz Research

Second, the decline is slaughtering rate in red meat (aside from cattle), along with the recent increase in poultry import tariffs are amongst the factors that have provided an increase in meat price inflation. Moreover, there is also an element of base effects as meat price inflation was fairly subdued in 2019.

Third, South Africa had a fairly good season in field crops and horticulture (fruit and vegetable) perspective, but that was only at the aggregate level. Some important vegetables which include potatoes saw prices rising in the past few weeks because of lower harvest in central and northern regions of South Africa. But this is all temporary. The outlook for the 2020/21 production season is positive, with prospects of La Nina induced rains.

Fourth, the increase in milk, eggs and cheese category of the food price inflation was a surprise as total raw milk purchases and supplies in the country have generally been higher than the previous five years, according to reports from the South African Milk Processors’ Organisation. Perhaps, this somewhat reflects the global dynamics, where milk prices have generally been at higher levels compared to 2019, according to the FAO Dairy Price Index.

Lastly, the acceleration in oils and fats price inflation is partly influenced by the weaker domestic currency in the past few months. South Africa remains a net importer of vegetable oils and therefore exposed to exchange rate risks. Moreover, the global vegetable oil prices have generally been at higher levels in recent months, boosted, in part, by the growing demand from China. These dynamics influenced price levels that we observed in the South African market.

Going forward

Nevertheless, this is all history, and many people are probably more interested in the outlook view going into 2021. Here I am generally optimistic that South Africa’s food price inflation might not exceed an average of 5% y/y in 2021. The expected Lan Nina rains will help boost the domestic harvest; but importantly harvest across Southern Africa, which will lessen pressure and demand for South African products. This, in turn, could lead to softer agricultural commodities prices and contain food price inflation at comfortable levels. The strengthening domestic currency also bodes well for products the country imports such as vegetable oils and fats.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo).

by Wandile Sihlobo | Feb 19, 2020 | Food Security

South Africa’s food prices increased at a relatively slower pace in January 2020 compared to December 2019. The data released this morning by Statistics South Africa shows that the country’s food price inflation was at 3.7% y/y in January 2020, while the previous month was 3.8% y/y. This deceleration, however, was not across the food basket. Only price inflation of bread and cereals; fish; and vegetables decelerated. But this was enough to overshadow the increases in meat; milk, eggs and cheese; oil and fats; fruit; sugar, sweets and desserts.

What we think will matter the most for the direction of food price inflation this year are developments in the grains and meat markets. These two food categories account for nearly two-thirds of South Africa’s food price inflation basket.

Firstly, the outlook for South Africa’s grain production is positive. Maize production could increase by, at least, 11% y/y to 12.5 million tonnes. The higher-end estimates point to a 14.0 million tonne harvest. What’s more, global wheat production, which South Africa is a net importer of, is set to be up 4% y/y to 764 million tonnes, according to data from the United States Department of Agriculture. This means grain-related product prices could be under pressure in the coming months.

Secondly, meat price inflation was subdued in 2019 because of the ban on red meat exports on the back of a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak at the start of that year. We are seeing a repeat of a similar situation this year following another foot-and-mouth disease outbreak at the end of 2019. This means South Africa’s meat prices could again remain at relatively lower levels for the greater part of this year. But the lower base effect of 2019 will mean that meat will not suppress the overall food price inflation in 2020 as much as in the previous year.

Against this backdrop, we believe South Africa’s food price inflation should hover around 4.0% in 2020 (food price inflation averaged 3.1% y/y in 2019). Under this scenario, the upside pressure will largely come from meat; and importantly, it will mainly be base effects in the case of red meat, and a possible slight uptick in poultry products prices. Grain prices should remain subdued on prospects of a good domestic maize crop, and bearish Chicago grains prices.

Exhibit 1: South Africa’s food price inflation

Source: Stats SA, Agbiz Research

Written for Agbiz.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo). E-mail: wandile@agbiz.co.za