by Wandile Sihlobo | Jul 6, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

The BRICS Summit is underway in Brazil and is scheduled to conclude tomorrow, July 7. There are many themes on the minds of the political leaders in this group, but one aspect that is certainly important for all is easing trade friction within this group. For the long-term sustainability of BRICS, there must be a stronger economic ambition that ties the grouping together beyond its political and geopolitical alignments.

Across all BRICS countries, researchers, policymakers, and businesspeople have been attempting to adapt and address the restrictions caused by the U.S. Liberation Day tariffs, and there remains profound uncertainty about the path ahead, as the 90-day pause comes to an end this coming week.

However, what the BRICS countries have not reflected on is also the prohibitive tariffs they place against each other, which limit intra-BRICS trade.

The blame, while correct, cannot be placed solely on the U.S. for its higher tariffs; the BRICS countries should also consider taking a serious look inward and assessing how they could deepen intra-trade and increase investments.

The ideas of this path have long been documented in the business arm of this grouping, the BRICS Business Council Forum’s various annual reports. Still, few of these ideas have made their way into the political groupings’ resolutions in a manner that profoundly changes the economic engagement landscape amongst these countries. The current environment necessitates such a strong approach.

Consider the South African agricultural sector, which, due to the lack of a trade agreement, faces higher tariffs in attractive BRICS member countries such as China. To name a few, South African macadamias face a 12% import tariff in China. The wine industry faces between 14%-20% in China, and many other products. In addition to higher tariffs, exporters also face phytosanitary barriers. I am singling out China here, but the same can be said about India, another major agricultural importer within BRICS.

For South Africa, agriculture is one of the key strategic industries for driving economic growth and revitalising rural communities. Notably, the sector cannot grow robustly without an expansion into new export markets. Already, the South African agricultural industry exports roughly half of its produce in value terms, amounting to approximately US$13.7 billion in 2024.

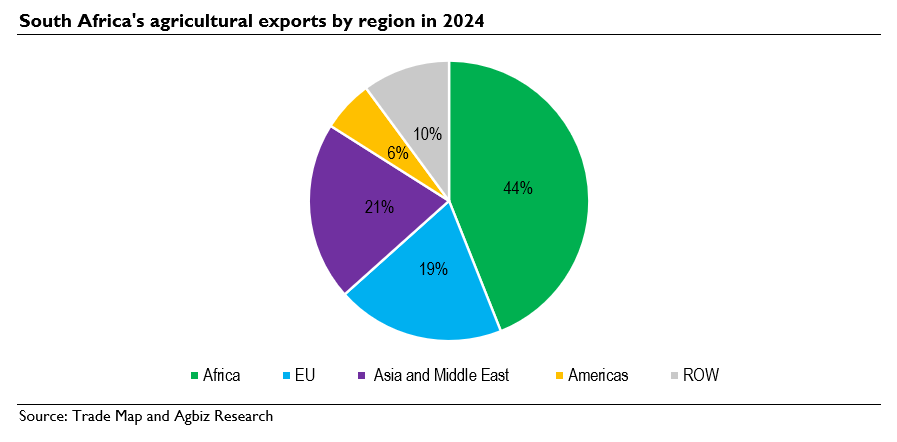

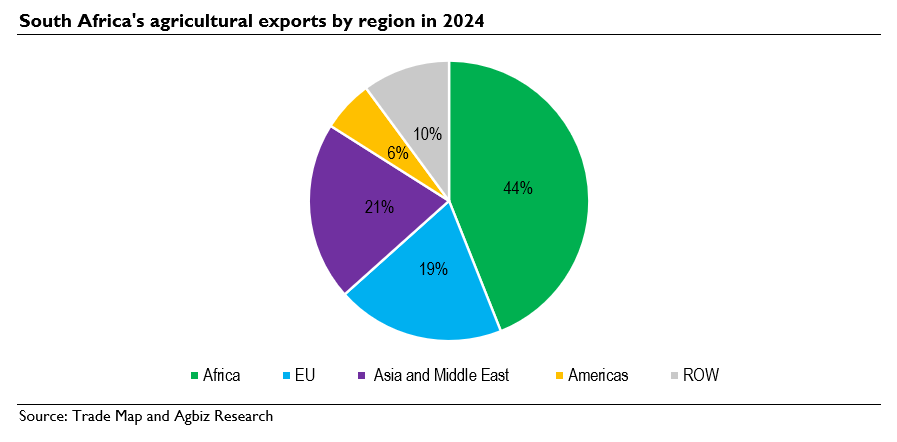

But the BRICS countries account for a small share of these exports. Roughly two-thirds of South Africa’s agricultural exports go to the African continent and the EU.

While China has signalled optimism and an intention to lower import tariffs for various goods from Africa, there is no demonstrable evidence of the actual path of implementing this, along with the timelines. Currently, it primarily serves as a political statement.

The BRICS grouping should then build on these political statements, and argue for a proper framework that technocrats and business can start refining, which can be launched in the next Summit in India as the BRICS trade agreement, which would encompass the agricultural sector, as this groping is a big market, accounting for roughly half of global agricultural imports, but filled mainly by non-BRICS members.

The U.S. authorities’ tough trade stance necessitates this approach to trade policy, and for the BRICS countries to expand trade avenues for their domestic businesses and alleviate the current friction within this group.

This economic ambition of deepening trade is vital for the long-term sustainability of BRICS.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Jul 4, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

In the current world of trade fragmentation, one area the BRICS countries should consider focusing on more in their deliberations this year is deepening intra-BRICS trade. For South Africa’s agriculture, this has been a central input in various discussions for some time, reflecting our desire to expand export markets to the BRICS countries, as well as the potential that lies in this region.

Currently, South African agricultural exports to the BRICS remain relatively low (at less than 10% of our agricultural exports to the world, which are US$13.7 billion as of 2024). The BRICS group is not a trade bloc, which partly explains our low agricultural penetration.

However, this may be an opportune time to change this reality and explore a more ambitious agricultural trade arrangement that aims to address the low intra-trade challenge in agriculture within this grouping.

What has proven to be a constraint in the past is not the low demand, but rather the relatively high import tariffs and some non-tariff barriers (phytosanitary barriers) within this group, which continue to distort agricultural trade.

The BRICS countries represent a substantial agricultural market, with annual imports exceeding US$300 billion. China and India are the major importers. The key agricultural products that the BRICS grouping imports include soybeans, palm oil, beef, maize, berries, wheat, cotton, poultry, pork, apricots, peaches, sorghum, rice, and sugar.

These are products that are produced at scale by some BRICS countries. Yet, the imports to other BRICS members typically originate from suppliers outside the grouping due to higher tariffs and phytosanitary barriers, among other issues.

China and India, amongst other countries, are of particular interest to South Africa for expanding agricultural exports. This is because they account for sizable agricultural import volumes, have growing populations, stable economies, and evolving consumer tastes.

South African policymakers’ engagements with their BRICS counterparts in Brazil over the coming week should include discussions on agricultural matters, with a particular emphasis on advocating for lower tariffs for specific products and addressing non-tariff barriers.

We all complain about the U.S.’s higher tariffs, but China has some issues as well. Consider the wine trade in China – countries like Australia and Chile have gained access to the Chinese market with 0% preferential tariffs. Meanwhile, South African producers face 14% import tariffs.

Of course, the main challenge is that we do not have an agricultural trade agreement with China. Hence, competition has been challenging for the wine industry and a range of farm products.

But it is for this very reason that I believe it is appropriate for BRICS countries to explore a possible agricultural trade agreement.

To me, trade conversations make more sense than the discussions of a “Grain Trade Exchange” that Russia is campaigning for. This Exchange, while understandable from a Russian perspective, brings limited value in terms of deepening trade, where the challenge remains tariffs rather than platforms. What Russia proposes will not fundamentally benefit all countries, but may ease financial flows, given the unique issues Russia faces since the start of the Black Sea War.

However, BRICS requires endurance and a long-term vision. For agriculture, this endurance and long-term vision can only exist if the underlying economics also support the interests of various businesses from the member countries. Those business interests would be better served if there were better and more favourable ways of trade within this bloc. Thus, I am of the view that the political conversations at BRICS should address this matter, among other significant themes.

I must also caution that my insistence on BRICS matters is not an attempt to diminish the trade and relationship we enjoy with the likes of the EU, Africa, the broader Asia and the Middle East, and the Americas. These remain valuable trading partners for our agricultural sector.

Our focus on BRICS agricultural trade opportunities is not to replace them, but to diversify export markets and enhance global competitiveness. Other strategic export markets for South Africa’s agricultural sector include South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Taiwan, Mexico, the Philippines, and Bangladesh.

This is an opportune time for BRICS to engage in an ambitious agricultural trade conversation that benefits all members.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Jul 2, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

Now that we are nearing July 8, which is the cutoff date for the 10% universal tariff the U.S. administration offered as a 90-day breather from the higher tariffs imposed on Liberation Day, there is some uncertainty about the path forward. South African businesses and the government have engaged, and continue to interact with, U.S. authorities regarding the path forward. However, the path forward remains unclear at this moment, although we would all like to see the continuation of the 10% tariffs rather than the 31% tariffs South Africa faced.

Observing this situation, the idea that some often offer is that we should channel our energies into export diversification to other new regions. The export diversification part is, of course, sound advice. However, we cannot completely abandon the U.S. market; it is vital to South Africa and crucial to us in the agricultural sector.

The export diversification comments typically point to China, suggesting that we should focus more on that area. Indeed, regular readers of this letter will be aware that China has been a primary focus for some time. From an agricultural perspective, China is a significant market, accounting for roughly 11% of global agricultural imports, which totalled US$218 billion in 2023.

However, accessing China is not as easy, despite the country’s optimistic statements about lowering import tariffs for goods from various African countries. Until there is clarity about this process and timelines, we continue to face higher tariffs in China and some phytosanitary barriers. These limits South African agricultural penetration into the Chinese market for now. Thus, South Africa remains a negligible player in the Chinese agricultural market, accounting for a mere 0.4% (US$979 million) of China’s agricultural imports of US$218 billion in 2023. These exports include a variety of fruits, wine, red meat, nuts, maize, soybeans, and wool.

Another matter that is also important to appreciate is that switching export markets is not as easy as stopping to sell citrus to Garry and selling it now to Bulelani. There is a business relationship development side and marketing that the private sector or export agents must establish, after the tariff issues and the phytosanitary matters are resolved.

There is also an issue of consumer taste and buying power per region, which all influence the demand for the various products that South Africa exports to specific markets.

Therefore, we need to build on an export diversification strategy, but it cannot be viewed as an overnight solution to avoiding the challenges in the U.S. market.

The export diversification strategy requires focus, firstly, from the government, and thereafter, time for the private sector to establish the necessary business relationships and address logistical challenges, especially in agriculture. It is partly for this reason that you may have heard me say that we must work to retain the market access we have in the U.S. for South Africa’s agricultural products, while also expanding our market access in various countries in the Middle East and Asia.

We cannot view other countries as the replacement of the U.S.; if anything, they can be an addition to our access in the U.S. over time. We also have significant potential for increased horticulture and other products that will require greater access to various export markets.

Importantly, the complexity of opening new export markets is also a matter that policymakers must underscore in their comments when guiding on trade matters at this time of heightened uncertainty in trade policy.

There also needs to be dedicated teams within the trade departments that work tirelessly on matters of export market expansion, so that policy adjustments are backed by actual work underway. Still, much of this takes time and is costly to businesses and other stakeholders. But it is vital and the only path to broadening our exports and strategically derisking our industries in the medium to long term.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Jun 24, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

South Africa’s agricultural export focus means the country must always keep an open eye for any potential new market expansion. One country that has consistently been on our radar is China. The country’s dominance in global agricultural imports, stable economy, large population, and current low penetration by South Africa’s agriculture make it an ideal area for expansion.

However, the non-existence of a preferential trade agreement in agricultural products has disadvantaged South Africa relative to its competitors, such as Australia, Peru, and Chile, among others, which access the Chinese market at a tariff-free rate or with low tariffs.

It is against this backdrop that I found the official announcement by the Chinese authorities that they would consider lowering import tariffs for various goods from African countries encouraging.

While no official details have been released yet, we view the message as consistent with what the official representatives of the People’s Republic of China have been communicating, particularly regarding agriculture. For example, in April, Mr Wu Peng, the current Chinese Ambassador to South Africa, stated that:

“…China and South Africa need to strengthen our bilateral trade and economic cooperation. The Chinese government welcomes more South African agricultural and industrial products to enter the huge Chinese market.”

China’s signalling the willingness to absorb more South African agricultural products is only the first step in what will likely be a long journey, as trade matters generally take time. Ideally, the following steps should be a clear and pragmatic plan for reducing import tariffs and removing phytosanitary barriers that certain agricultural products continue to encounter in the Chinese market.

Indeed, the work must be led by South Africa’s Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition, as well as the Department of Agriculture, and at specific points, also the Department of International Relations and Cooperation. This will help ensure that China proceeds beyond statements to actual business collaboration.

South Africa remains a small share in the Chinese list of agricultural suppliers, at about 0,4%. However, this current access in China is vital for the wool and red meat industry. China accounts for roughly 70% of South Africa’s wool exports.

There is a progressive increase in red meat exports, even though animal diseases currently cause glitches. The focus should be on expanding this access by lowering duties and other non-tariff barriers to encourage more fruit, grain, and other product exports to China.

Still, it is essential to emphasise that the focus on China is not at the expense of existing agricultural export markets and relationships. Instead, China offers an opportunity to continue with export diversification.

The Trade Map data show that China is among the world’s leading agricultural importers, accounting for 9% of global agricultural imports in 2024 (before 2024, China had been a leading importer for many years). The US was the world’s leading agricultural importer in the same year, accounting for 10% of global imports. Germany accounted for 7%, followed by the UK (4%), the Netherlands (4%), France (4%), Italy (3%), Japan (3%), Belgium (3%) and Canada (2%).

It is this diversity of agricultural demand in global markets that convinces us that South Africa’s agricultural trade interests cannot be limited to one country but should be spread across all major agricultural importers.

Importantly, the approach of promoting diversity and maintaining access to various regions has been a key component of South Africa’s agricultural trade policy since the dawn of democracy.

For example, in 2024, South Africa exported a record US$13.7 billion of agricultural products, up 3% from the previous year. These exports were spread across the diverse regions. The African continent accounted for the lion’s share of South Africa’s agricultural exports, with a 44% share of the total value.

As a collective, Asia and the Middle East were the second-largest agricultural markets, accounting for 21% of the share of overall farm exports. The EU was South Africa’s third-largest agricultural market, accounting for a 19% share of the market. The Americas region accounted for 6% of South Africa’s agricultural exports in 2024. The rest of the world, including the United Kingdom, accounted for 10% of the exports.

In brief, China’s indication of its willingness to lower import tariffs is a welcome development. However, it will only become more substantial once more information becomes available.

From a South African side, the relevant government departments should consider, through the local Embassy, sending an enquiry about unlocking this process. Ultimately, China is one of the focus areas in South Africa’s long-term agricultural export diversification strategy, and any opportunity to further this plan should be pursued vigorously.

Importantly, while China’s offer looks generous, a country like South Africa needs to draw appropriate lessons from experience. Unilateral duty-free, quota-free market access is a double-edged sword: in the short to medium term, they can help a country increase the share of its exports in a significant market, but since these are not anchored in reciprocity, the largesse can disappear if there are frictions between the two parties, for example, over geopolitics.

In short, non-reciprocal arrangements can lead to dependence and can easily be exploited by the benefactor as a means of political leverage to achieve strategic ends. While South Africa—and indeed African countries—should take advantage of this opportunity, we must aim to conclude a bilateral trade agreement with China that guarantees predictability, certainty, and durability.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Jun 12, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

I’m at the airport in Kimberly in the Northern Cape as I type this, and I just saw the news that China aims to lower import tariffs on a range of goods from various African countries.

We are yet to receive more details on China’s intentions to lower import tariffs for various African countries. What is worth emphasising for now is that, from a South African agricultural perspective, this would be a welcome development.

China has profound importance in global agriculture. In 2023, China was a leading importer, accounting for 11% of global agricultural imports, with imports valued at US$218 billion. The leading suppliers of farm products to China are Brazil, the U.S., Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, Canada, Vietnam, France, Russia, Argentina, Chile, Ukraine, the Netherlands, and Malaysia.

However, China has been on a journey to diversify its agricultural exports beyond these suppliers, which has accelerated following the U.S. initial tariffs in 2018 and is ongoing in 2025.

South and Latin American countries, as well as Australia, have been the primary beneficiaries of China’s diversification strategy so far.

But South Africa must also be part of this conversation. And what the Chinese authorities have signalled is a starting point for a deeper conversation on agricultural trade.

The first step will have to be for South African authorities to approach China to present a range of products that can be exported, and then build from there.

South Africa remains a negligible player in the Chinese agricultural market, accounting for a mere 0.4% (US$979 million) of China’s agricultural imports of US$218 billion in 2023. These exports include a variety of fruits, wine, red meat, nuts, maize, soybeans, and wool.

However, there is room for more ambitious agricultural export efforts.

The South African agricultural sector, comprising organised agriculture and researchers, consistently emphasises the need to lower import tariffs in China and remove phytosanitary constraints on various products.

There is now a pathway to have a productive conversation about this matter and move with speed. Once more details are available on tariffs, we will also need to examine the phytosanitary issues related to agriculture.

Overall, this is welcome news.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Jun 12, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

In a year where trade has dominated the headlines since the U.S. started imposing higher tariffs against its trading partners, agricultural export activity is worth paying close attention to. Encouragingly, the start of the year has remained positive for the sector. In the first quarter of 2025, South Africa’s agricultural exports totalled US$ 3.36 billion, up 10% from the same period a year ago, according to data from Trade Map. This is a function of both higher volumes of various product exports and better commodity prices.

The products that dominated the exports list in the first quarter were mainly grapes, maize, apples, pears, apricots, cherries, peaches, wine, wool, fruit juices, nuts, dates, avocados, pineapples, and beef, among other products. While the ports remain a challenge and require further improvement and investment, the agricultural export season in the first quarter experienced less friction than in the recent past.

From a regional perspective, the African continent maintained the lion’s share of South Africa’s agricultural exports in the first quarter of 2025, accounting for 45% of the total value. The products leading the exports list in the African continent were maize, maize meal, sugar, apples and pears, fruit juices, wine, soybean oil, sunflower oil, oilcake, and wheat, amongst other products.

The EU was South Africa’s second-largest agricultural market, accounting for a 23% share of the market. Grapes, apricots, cherries, peaches, nectarines, wine, apples and pears, wool, dates, figs, pineapples, avocados, mangos, guavas, fruit juices, and nuts were amongst the primary agricultural products South Africa exported to the EU in the first quarter of 2025.

As a collective, Asia and the Middle East were the third-largest agricultural markets, accounting for 16% of the total agricultural exports in the first quarter of 2025. The exports to this region primarily included apples and pears, grapes, wool, beef, apricots, cherries, peaches, nectarines, citrus, lamb, nuts, and strawberries, among other products.

The Americas region accounted for 6% of South Africa’s agricultural exports in the first quarter of the year. The main exported products include grapes, apricots, cherries, wine, fruit juices, nuts, apples, pears, and citrus.

Given ongoing concerns about South Africa’s participation in the AGOA (Africa Growth and Opportunity Act) trade arrangement and the current higher tariffs imposed by the U.S., it is worth highlighting that South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. were still 4% in the first quarter of 2025 (which is part of the 6% exports to the Americas region we mention above).

The rest of the world, including the United Kingdom, accounted for 10% of South African agricultural exports in the first quarter of 2025.

South Africa does not engage in one-way trade. The country imports various agricultural products. In the first quarter of 2025, South Africa’s agricultural imports totalled US$ 1.94 billion, a 19% increase year-over-year, according to data from Trade Map. The increase resulted from higher value and volume of major products South Africa imports, such as wheat, palm oil, rice, poultry, and whiskies.

As we have argued before, South Africa lacks favourable climatic conditions for growing rice and palm oil and thus relies on imports of these products. Regarding wheat, South Africa imports nearly half of the annual consumption.

Meanwhile, imports account for around 20% of the annual domestic poultry consumption. Given the current ban on Brazil’s poultry imports, we may see an increase in volume from other regions or a recovery in domestic production, as the local producers indicate.

Subsequently, when we account for the exports and imports, South Africa’s agriculture sector recorded a trade surplus of US$ 1.42 billion in the first quarter of 2025, down 1% from the previous year.

Policy considerations

In the current environment of heightened geoeconomic tensions, South Africa’s export-oriented agricultural sector must work to maintain its current export markets and expand into new ones. The focus for both policymakers and agribusinesses and organised agriculture should be on the following aspects:

First, South Africa should maintain its focus on improving logistical efficiency. This entails investments in port and rail infrastructure, as well as improving roads in farming towns.

Second, South Africa must work diligently to maintain its existing markets in the EU, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas.

Lastly, South Africa should expand market access to some key BRICS countries, such as China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | May 25, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

This past week, South Africa’s Deputy President, Paul Mashatile, was in France, amongst other things, to promote economic cooperation between the countries.

Mashatile’s visit did not receive much attention as the developments of the Oval Office continued to be the primary focus. But at its core, the work he was doing in France, and by extension, the greater EU, is aligned with the US visit by the South African President, Cyril Ramaphosa, to seek to strengthen relations, attract investment and deepen trade.

While we don’t often discuss it as much, the EU is one of South Africa’s important trading partners. If we focus on agriculture and assess the EU’s participation, it is very encouraging. In the US$13,7 billion of South Africa’s agricultural exports in 2024, the EU accounted for 19% and was the third-largest agricultural trading partner after the African continent and the collective Asia and the Middle East regions.

Citrus, grapes, wines, dates, avocados, pineapples, fruit juices, apples and pears, berries, apricots and cherries, nuts, and wool were amongst the top agricultural products South Africa exported to the EU in 2024.

And yes, the South African agricultural sector has faced various challenges in the EU market, particularly in citrus. For example, the EU recently used non-tariff barriers by alleging a “False codling moth”, a citrus pest, in South Africa and requiring citrus products to be kept at certain temperatures before accessing the EU market.

This issue happened while South Africa had already treated the products to eliminate the chances of such a pest occurrence. In a way, one could argue that this was a subtle form of protecting Spanish farmers, who are also major citrus producers within the EU market.

Still, this does not change the fact that many agricultural value chains in South Africa have prospered over the years, leaning on the EU market. Importantly, as in the past, we all want to resolve citrus friction and for the countries to affirm a long-term better trading environment for all products.

In essence, while South Africa works to resolve and deepen trade with regions such as the US, where there are higher tariffs, and China, a vital market, but with higher tariffs and phytosanitary barriers, we should not forget the existing markets that have helped us prosper.

We should continually engage with the EU, UK, Middle East, and the greater African continent to deepen relations, trade and investment.

The continuous conversation about agricultural export diversification within BRICS nations, such as China, India, and Saudi Arabia, is not a replacement for the long-existing relations with the EU and other trading partners.

Thus, Deputy President Mashatile’s visit to France was vital in strengthening relations broadly, not just for the farming sector but also for other sectors of the economy and investment.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | May 16, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

Amid escalating trade tensions worldwide, the appropriate posture for SA agriculture on trade is not to prefer one country over another, but to seek ways to multiply friendships and trade relations.

China’s recent public statements about its interest in deepening agricultural trade with SA should not be seen as an avenue to replace US exports or other trading partners. Instead, this offers an opportunity to continue with export diversification.

According to Trade Map data, China is among the world’s leading agricultural importers, accounting for 9% of global agricultural imports in 2024 (before 2024, China was a leading importer for many years). The US was the world’s leading agricultural importer in the same year, accounting for 10% of global imports.

Germany accounted for 7%, followed by the UK (4%), the Netherlands (4%), France (4%), Italy (3%), Japan (3%), Belgium (3%) and Canada (2%).

SA’s agricultural trade interests should spread across all major agricultural importers in such an environment.

This is a policy approach SA has practised since the dawn of democracy, and the export activity now illustrates it. For example, in 2024, SA exported a record $13.7bn of agricultural exports, up 3% from the previous year. These exports were spread across diverse regions.

Africa maintained the lion’s share of SA’s agricultural exports, accounting for 44% of the total value.

Collectively, Asia and the Middle East were the second-largest agricultural markets, accounting for 21% of the share of overall farm exports. The EU was SA’s third-largest agricultural market, with a share of 19%.

In 2024, the Americas accounted for 6% of SA’s agricultural exports, while the rest of the world, including the UK, accounted for 10%.

The products exported differed slightly across the regions. Exports to the rest of Africa primarily consist of grains, sugar, apples and pears, fruit juices, wine, soya bean oil, sunflower oil, oilcake and rice, among other products.

The Asian and Middle-Eastern regions have similar products, with the addition of beef, mutton and wool.

Meanwhile, exports to the EU and UK are mainly citrus, grapes, wine, dates, avocados, pineapples, fruit juices, apples and pears, berries, apricots and cherries, nuts and wool. This again confirms that products perform differently across markets, further supporting a view of maintaining wide access to a range of export regions.

China remains an attractive area for SA, but signalling the willingness to absorb more SA agricultural products is only the first step. The next steps should be a realistic reduction of the import tariffs and the removal of the phytosanitary barriers that certain agricultural products continue to encounter in the Chinese market. Indeed, the work must be led by the Department of Trade, Industry & Competition, the Agriculture Department, and, at some points, also the Department of International Relations & Co-operation.

However, China must also demonstrate an effort to collaborate beyond the statements. While China is the second-largest agricultural market, SA has a small share in the Chinese list of agricultural suppliers, at about 0.4%.

However, this access in China, in the same view as citrus, wine grapes, nuts and wine in the US market, is vital for the wool and red meat industries. China accounts for about 70% of SA’s wool exports. There is a progressive increase in red meat exports, even though animal diseases cause glitches.

Focus should be on expanding this access by lowering duties and other non-tariff barriers in the Chinese market.

SA’s agriculture sector should continue to insist on strengthening relations with all existing trading partners and expanding into new markets.

Written for and first appeared in the Business Day.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)