by Wandile Sihlobo | Sep 22, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

While concerns about deeper access for agricultural products into the U.S. market continue to linger, the activity so far has remained encouraging. South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. increased by 26% in the second quarter of 2025, from the same period a year ago, at US$161 million.

It appears that some exporters may have taken advantage of the 90-day pause of the higher tariffs and exported more volume than usual during that period.

The composition of the products remains unchanged, primarily consisting of citrus wine, fruit juices, and nuts, among other typical agricultural exports to the U.S.

The fact that South Africa generally has a large fruit harvest also contributed to this enormous increase, which far surpassed the average typical quarterly growth in exports to the U.S., which is about 9%.

Also worth highlighting is that the rise underscores in a way the importance of the U.S. market for some producers, while it remains somewhat smaller from a national perspective. South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. were still 4% in the second quarter of 2025.

(South Africa’s agricultural exports to the world market totalled US$3.71 billion in Q2, up 10% from the same period a year ago).

Again, the 4% share of the U.S. in the overall South African agricultural exports is not a small value, as few specific industries are primarily involved in these agricultural exports. These are mainly citrus, grapes, wine, and fruit juices.

Since the start of AGOA, the percentage share of South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. has remained at these levels. From now on, a great deal hinges on whether South Africa succeeds in securing favourable trade terms with the U.S. The future performance of the exports to the U.S. will rely mainly on the success of the ongoing conversations between the two countries.

The export diversification we are discussing is not about replacing the U.S. but rather adding to it. We have a growing sector that requires more export markets in the future; thus, this issue of export diversification is more urgent right now.

Our primary focus is to work diligently to maintain our existing markets in the EU, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas. It is also crucial for South Africa to expand market access to some key BRICS countries, such as China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt.

The emphasis on the BRICS grouping should be on the need to lower import tariffs and address artificial phytosanitary barriers that hinder deeper trade within this grouping. The discussion in BRICS should move beyond the general rhetoric of intentions to meaningful trade arrangements.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Sep 21, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

The challenges that American farmers face, struggling with exports of their soybeans and other crops, show once again the importance of open and fair trade. The current higher U.S. tariffs, along with retaliatory measures by trading partners, pose a problem for everyone.

For example, China, which is not only a significant market for U.S. farmers but also imports roughly half of the world’s traded soybeans, has progressively shifted its suppliers, now sourcing more produce from South America and Latin America.

The renewed trade friction between the countries has only accelerated the trend and left the U.S. farmers in a challenging position with one of their key export markets.

China learned from the first time President Trump levied higher tariffs on them, and their consequent retaliatory tariffs, and started shifting its sources for some of its agricultural products. We now read various articles that sum up the challenge faced by U.S. farmers as:

“Across the US, farmers describe increasingly dire circumstances stemming from a confluence of factors — trade wars, Trump’s immigration crackdown, inflation and high interest rates.”

Clearly, the trade war has not only challenged farmers in terms of export markets, but they also face labour shortages in some regions. The anti-immigration policy has arguably been unsuitable for agriculture, which, to some extent, relies on foreign labour.

Of course, the challenges differ from farmer to farmer and by region. However, it is probably fair to say that so far, the U.S.’s higher tariffs and retaliatory measures by some trade partners are causing more damage to farmers.

There is perhaps a message here for South Africans who care about agriculture, a recognition that the trade friction is causing headaches for all. For us, it presents profound uncertainty for exporting farmers and agribusinesses (to the U.S.), mainly citrus, table grapes, ostrich, wine, and nuts, amongst others. It has also introduced volatility into the global grains and oilseed markets, which in turn affects our grains market.

Equally, the U.S. farmers face economic pain as some of their key markets have retaliated. The core message is that open and fair trade is the only good path for major agricultural producers, and this includes us in South Africa.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Sep 18, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

It would be helpful if the Zimbabwean government could reverse its current ban on maize imports. We understand that it is in place to protect domestic farmers, to some extent, during the months following harvest. But there is growing evidence that the supply is constrained. Some milling firms already face challenges because of the maize shortage.

As we argued a few days ago, Zimbabwe likely doesn’t have sufficient maize supplies for their annual needs. We believe, based on data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), that Zimbabwe’s maize production is around 1.3 million tonnes. Given the annual consumption of 2.0 million tonnes, they naturally need about 700,000 tonnes to fulfil their needs.

However, we had anticipated that the needs would be more severe by the end of the year and into the first quarter of 2026. We thought the current harvest would carry them for now, albeit with artificially higher prices in the context of a ban on imports of affordable maize from the world market. But it appears that the supplies are constrained already.

Under this context, while it is understandable that the Zimbabwean government wants to protect farmers, it would be beneficial for them to consider lifting the ban now and supporting the households.

We discussed the details of the issue in our AgriView episode last week, which you can watch here.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Sep 16, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

In a year where trade continues to dominate headlines after the U.S. started imposing higher tariffs against its trading partners, we take a look at South Africa’s recent agricultural exports data to gauge the early impact of the changing trade environment.

Encouragingly, the start of the year has remained positive for the sector. After solid export activity in the first quarter of the year, South Africa’s agricultural exports totalled US$3.71 billion in Q2, up 10% from the same period a year ago. This is again a function of both higher volumes of various product exports and better commodity prices.

The products that dominated the exports list in the second quarter of the year were mainly citrus, apples and pears, maize, wine, nuts, fruit juices, dates, pineapples, avocados, grapes, and wool, amongst other products. While there remains a need for further improvement in the efficiency of the ports, there has been a material improvement compared to recent years. Agricultural export activity in the second quarter experienced less friction than in the recent past.

From a regional perspective, the African continent maintained the lion’s share of South Africa’s agricultural exports in the second quarter of 2025, accounting for 40% of the total value. The products leading the exports list in the African continent were maize, maize meal, apples and pears, sugar, fruit juices, wheat, wine, soybean oil, and sunflower oil, amongst other products.

The EU was South Africa’s second-largest agricultural market, accounting for a 22% share. Citrus, apple and pears, dates, pineapples, avocados, guavas, mangos, wine, grapes, and nuts were amongst the primary agricultural products South Africa exported to the EU in the second quarter of 2025.

As a collective, Asia and the Middle East were the third-largest agricultural markets, accounting for 21% of the total agricultural exports in the second quarter of 2025. The exports to this region primarily included citrus, apples and pears, nuts, wool, maize, beef, mutton, wine, berries, and fruit juices, among other products.

The Americas region accounted for 7% of South Africa’s agricultural exports in the second quarter of the year. The main exported products include citrus, fruit juices, wine, nuts, apricots, apples, pears, and grapes. Given ongoing concerns about the higher tariffs South Africa faces in the U.S., it is worth highlighting that some exporters may have taken advantage of the 90-day pause of the higher tariffs and exported more volume than usual during that period.

Notably, South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. surprisingly increased by 26% in the second quarter of 2025, from the same period a year ago, at US$161 million. The composition of the products hasn’t changed; it is mainly citrus wine, fruit juices, and nuts, amongst other typical agricultural exports to the U.S. The fact that South Africa generally has a large fruit harvest also contributed to this huge increase, which far surpassed the average typical quarterly growth in exports to the U.S., which is about 9%.

Also worth highlighting is that the rise underscores in a way the importance of the U.S. market for some producers, while it remains somewhat smaller from a national perspective. South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. were still 4% in the second quarter of 2025 (which is part of the 7% exports to the Americas region we mentioned above).

Again, the 4% share of the U.S. in the overall South African agricultural exports is not a small value, as few specific industries are primarily involved in these agricultural exports. These are mainly citrus, grapes, wine, and fruit juices. Since the start of AGOA, the percentage share of South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. has remained at these levels.

From now on, a great deal hinges on whether South Africa succeeds in securing favourable trade terms with the U.S. The rest of the world, including the United Kingdom, accounted for 10% of South African agricultural exports in the second quarter of 2025.

The country also imports various agricultural products. In the second quarter of 2025, South Africa’s agricultural imports totalled US$1.81 billion, a 5% decline year-over-year, according to data from Trade Map. The result is from slightly lower value and volume of major products South Africa imports, such as wheat, palm oil, poultry, and whiskies.

As we have highlighted before, South Africa lacks favourable climatic conditions for growing rice and palm oil and thus relies on imports of these products. Regarding wheat, South Africa imports nearly half of the annual consumption. In the Free State province, which was once one of the country’s major wheat-growing regions, production has declined notably over time due to unfavourable weather conditions and profitability challenges of wheat compared to other crops. Meanwhile, imports account for around 20% of the annual domestic poultry consumption.

Subsequently, when we account for the exports and imports, South Africa’s agriculture sector recorded a trade surplus of US$1.90 billion in the second quarter of 2025, up 29% from the previous year. The higher exports and the decline in imports are the major boost to this better trade surplus.

Policy considerations

In the current environment of heightened geoeconomic tensions, South Africa’s export-oriented agricultural sector must work to maintain its current export markets and expand into new ones. The focus for both policymakers and agribusinesses and organized agriculture should be on the following aspects:

First, South Africa should maintain its focus on improving logistical efficiency. This entails investments in port and rail infrastructure, as well as improving roads in farming towns. Second, South Africa must work diligently to maintain its existing markets in the EU, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas.

Lastly, the South African Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, the Department of International Relations and Cooperation, and the Department of Agriculture should lead the way in expanding exports to current markets and exploring new ones. South Africa should expand market access to some key BRICS countries, such as China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. The emphasis on the BRICS grouping should be on the need to lower import tariffs and address artificial phytosanitary barriers that hinder deeper trade within this grouping. The discussion in BRICS should move beyond the general rhetoric of intentions to meaningful trade arrangements.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Sep 15, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

The economists Daan Steenkamp and Jacques Quass de Vos make an important observation about the shortfalls in South Africa’s geoeconomic approach in their latest Business Day article (“SA’s geoeconomic gamble is not paying off”, September 15).

Among other things, they argue correctly that the BRICS grouping has provided limited economic benefit to South Africa. The exception is China, with which South Africa has deeper trade relations, though more could be done in agriculture and other sectors of our economy if we had a free trade agreement.

However, the path forward in this challenge is not necessarily to abandon the BRICS bloc but to elevate its economic ambition. BRICS remains a loose, informal grouping with no sound economic or trade approach that keeps the countries together.

In fact, when one considers the intra-BRICS trade, it quickly becomes clear that little is happening in the grouping beyond political matters, with China again being an exception for many countries on trade matters. The constraining factor, as a result of the lack of a BRICS free trade agreement, is the observation that Steenkamp and De Vos make about the low exports and investment in this region.

Much of South Africa’s economic relationships and investments are with the Western world. But South Africa doesn’t have the luxury to choose either or. Our approach should be to balance and retain our existing trading partners in Europe, the Americas, and other parts of the world, while simultaneously pushing for an ambitious trade agreement within BRICS and exploring ways to attract investments.

Our focus should be on bettering South Africa by skilfully navigating the complex geoeconomic environment of the day.

In essence, we should (economically at least) reach out to and be friends with all who want to do business with us. India, by the way, is likely to be a global engine of growth for the next two decades or so, as its per capita GDP catches up. So, deepening trade is key to long-term progress.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Sep 14, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

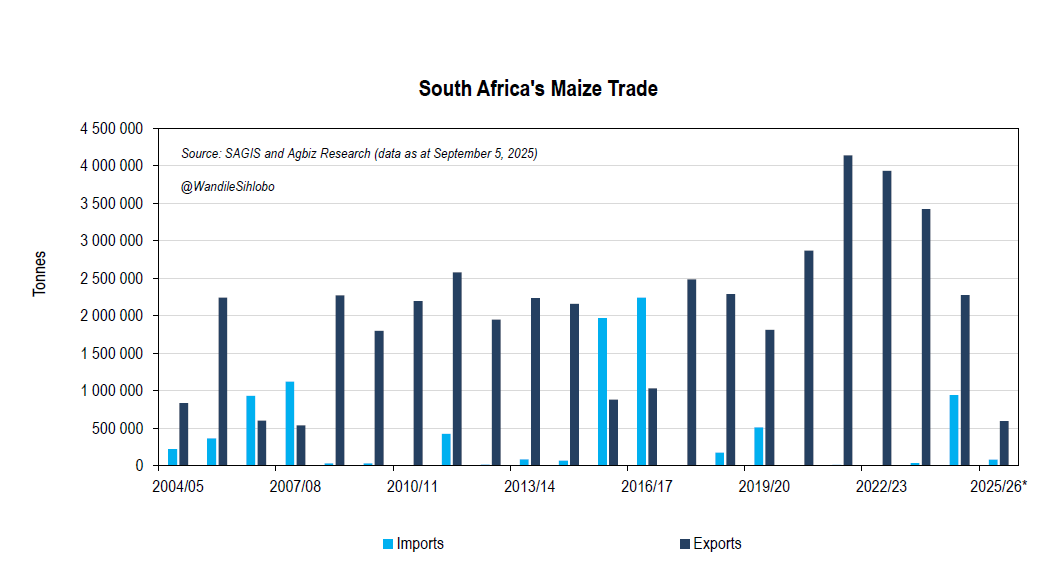

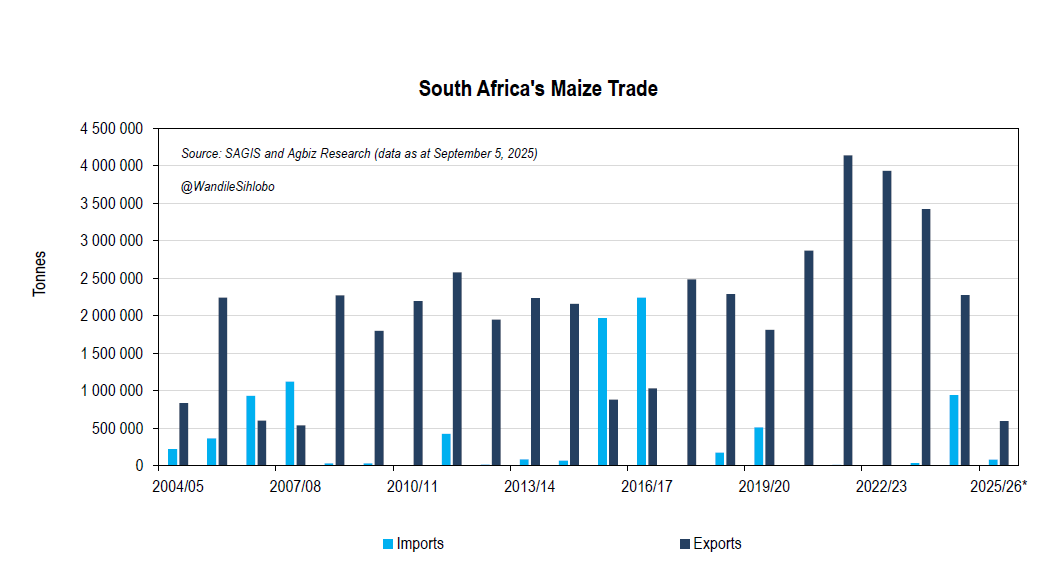

One thing that probably requires some clarification with South Africa’s maize trade at the moment is that we haven’t necessarily stopped imports. Yes, imports. But this does not mean we have shortages per se.

South Africa has one of the best agricultural seasons, albeit with some quality issues with white maize. The volumes are solid.

However, the livestock and poultry producers in coastal regions of South Africa sometimes compare feed prices here at home and elsewhere in the world, and take advantage of relatively lower prices from other origins. But such opportunistic yellow maize imports happen rarely in seasons of abundance like this one.

I am raising this issue because those who closely examine our maize trade data will notice that, to date in the 2025-26 marketing year (corresponding to the 2024-25 production season), South Africa has imported 77,768 tonnes of yellow maize from Argentina. These are opportunistic imports and don’t necessarily mean that we experienced some shortages. The yellow maize is likely for animal feed production, as has been the case in the past.

As all this is happening, the exports from South Africa to the various destinations in the world also continue. For example, in the week of September 5, South Africa exported 23,811 tonnes of maize, all to the Southern African region. This placed South Africa’s 2025-26 maize exports at 592,994 tonnes, out of the expected seasonal exports of 2.12 million tonnes. The current marketing year only ends in April 2026. About 60% of South Africa’s maize exports so far are yellow maize.

The various regions South Africa has exported maize to this year, aside from the broader African continent, include Taiwan, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, South Korea and Venezuela. We will likely see continuous exports to these regions. We are not even at half of South Africa’s maize export season for the year, which is 2.12 million tonnes.

The next couple of months may likely be quiet, particularly in the Southern Africa region, as some countries rely on the recently harvested domestic supplies for now.

We will likely see more robust export activity later in the year once farmers have completed the harvest and there is grain in the silos for export. This is also a time when we anticipate that countries like Zimbabwe, which currently have an import ban on maize, will return to the market to buy some South African maize to fulfil their domestic needs.

South Africa has a robust maize production season. The 2024-25 maize harvest is estimated at 15.80 million tonnes, a 23% increase year-on-year, primarily due to expected annual yield improvements. This harvest is well above the long-term production levels in South Africa.

Importantly, these forecasts are well above South Africa’s yearly maize needs of approximately 12.00 million tonnes, implying that South Africa will have a surplus and remain a net exporter of maize.

Therefore, when one hears about yellow maize imports, this is a vital context that one must remember. We are not experiencing any challenges with domestic maize supplies or higher domestic prices.

Important: South Africa’s maize prices have declined notably over time as a result of ample domestic harvest. At the end of the week of September 12, 2025, South Africa’s white maize spot price was down roughly 28% from a year ago, trading under R4,000 a tonne. At the same time, South Africa’s yellow maize spot price was down by 7% from a year ago, trading at levels around R3,600 per tonne.

Therefore, the imports are primarily opportunistic, not because South Africa’s maize is expensive per se. We also expect them to be limited, as the domestic harvest is abundant.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Aug 31, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

Some countries in the Southern Africa region have some maize supplies from the recent harvest. South Africa is likely to see its exports slow down for now, particularly to countries in the region. We may continue to see encouraging export volumes to the Far East and other areas of the world.

Still, towards the end of the year and into 2026, when domestic supplies are somewhat depleted in the various countries in the region, they will return to the market and import maize. This was not the case last season, as most countries were negatively affected by the drought and required massive imports throughout. This time around, we had favourable summer rains that supported grain production across the Southern Africa region.

It is this brief context that we must keep in mind when observing maize export data these days. The exports aren’t down because our maize is expensive; in fact, maize prices have been under pressure in recent weeks as farmers delivered decent maize volumes to silos, and South Africa expects an ample harvest of 15.80 million tonnes, which is 23% higher than the crop for the 2023-24 season.

It is against this background that, for example, maize exports for the past week were mediocre. For example, South Africa exported 14,428 tonnes of maize in the week of August 22, all of which was destined for the Southern African region.

This placed South Africa’s 2025-26 maize exports at 553,808 tonnes, out of the expected seasonal exports of 2.12 million tonnes. The current marketing year only ends in April 2026.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Aug 30, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

The US’s decision to impose a steep tariff on imports from SA has ignited an urgent discussion on how best to minimise the effect of these measures on various exporting sectors, including agriculture.

In addition to the ongoing conversation about expanding SA’s agricultural export markets, we believe the country must accelerate its efforts to promote agricultural products in international markets.

The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition typically leads the various trade shows, supported by the private sector and other government agencies. These trade shows, more than ever, must be channelled to the priority regions for our export expansion plan.

The visibility of the high-quality variety of SA agricultural products is key for marketing purposes and informing consumers and retailers in various countries about the products they could source from SA. We believe such marketing work and formal trade conversations would be a powerful approach for ensuring the penetration of the SA agricultural products into a range of new markets.

Importantly, government officials in SA, particularly those in the Department of Agriculture responsible for export-related matters, should also share a sense of urgency for promoting exports. They should work collaboratively to assist exporting businesses rather than creating more bureaucratic hindrances, while the global interest is established.

We have heard of a few cases where there is often a lack of collaboration from the domestic side, while international consumers are open to SA products, particularly for some processed products. A case in point is the pet food industry, where local authorities often move much more slowly than exporters would like.

While SA is thriving in Africa and Europe, which account for roughly two-thirds of its agricultural exports in value terms, there remains room for expansion in other regions. Asia the Middle East are some of the areas we continue to see greater opportunity for export expansion. During various government visits to these regions, bringing the private sector along for deeper business engagement and optimising existing structures for trade shows should be explored.

Also critical in this trade conversation is the appropriate staffing of embassies in the key export markets. The support staff at the embassies must have the proper skillset to assist the SA businesses in their commercial activities. Indeed, the guidelines of the work must be outlined in SA’s economic diplomacy strategy, spelling out both the country’s economic and commercial diplomacy focus. Such a vision and strategy would then guide the work of the support staff.

The discussions on trade policy cannot be limited to the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition alone. They require a comprehensive approach to ensure the agreements are rooted in the aspirations of business and national priorities. Importantly, these engagements create a platform for executing trade and increasing the visibility of SA agricultural products in the world market.

This sector of the economy still has potential to create more jobs at the primary level and in the value chains. However, the employment and sustainability of the industry depend on a comprehensive growth approach. Maximising trade opportunities is key to ensuring that we continue on an export-led growth approach.

There is also a need to ensure that the exporting industries are well supported. As such, a deeper involvement of officials in SA’s various embassies is even more critical as the country strengthens its export approach, particularly for agricultural and other exporting sectors of the economy.

This new path requires a well-communicated and supported economic diplomacy strategy for the country, along with the alignment of all necessary interventions to support it. All these priorities are in recognition of the role of agriculture in supporting SA’s economic growth.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)