by Wandile Sihlobo | Dec 13, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

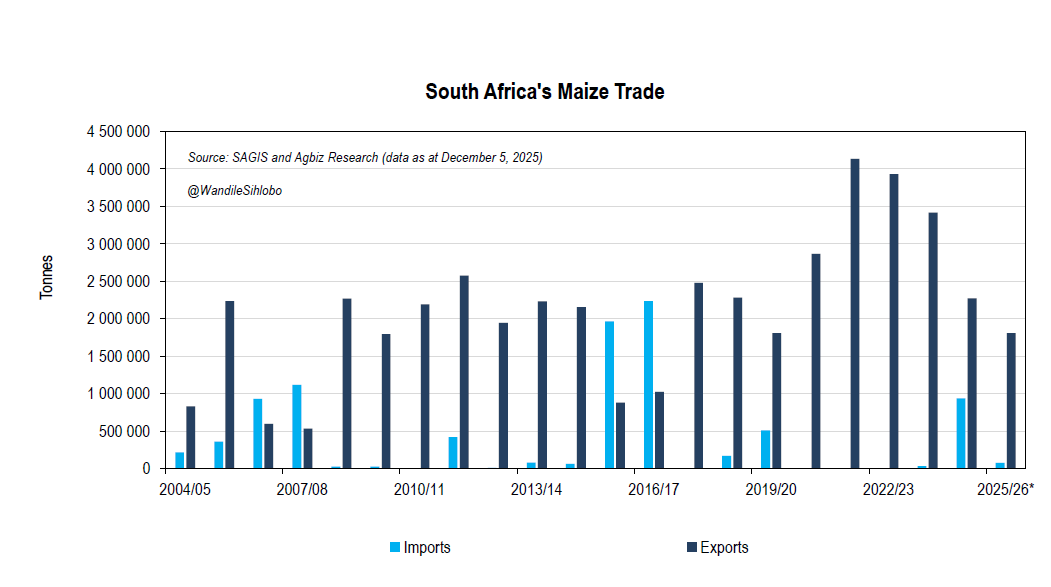

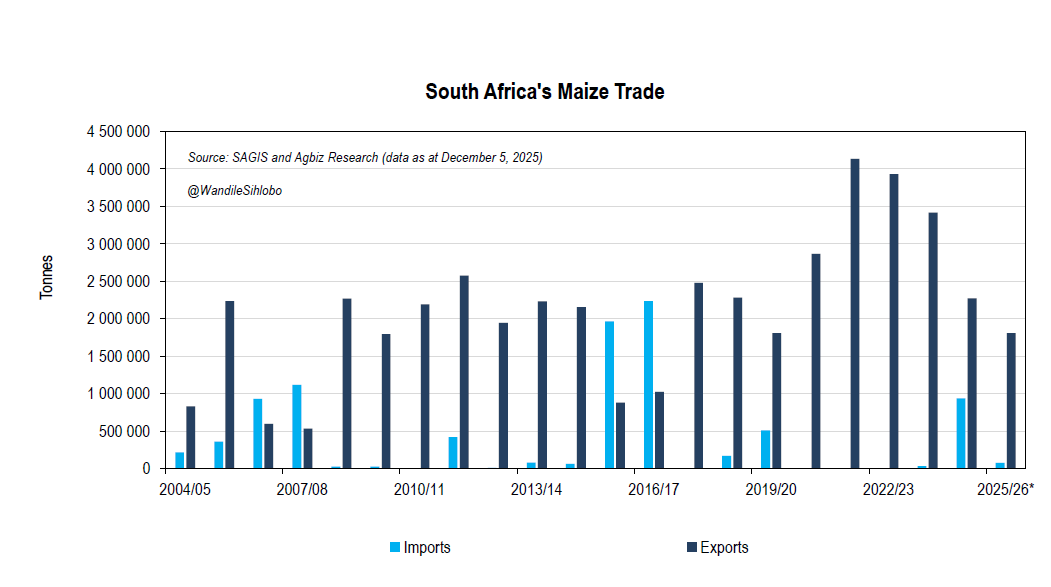

We knew from the start of the 2024-25 season that South Africa would remain a net exporter of maize, as the crop looked promising. With the 2024-25 production season over, with an ample harvest of 16.44 million tonnes, up 28% year-on-year and the second-largest maize crop on record, the export figures are also being revised up.

South Africa will likely export 2.4 million tonnes of maize in the 2025-26 marketing year, which ends in April 2026. This marketing year corresponds with the 2024-25 production season.

This is a slight upward revision from the last export forecast of 2.2 million tonnes. Still, it is down mildly from the 2.8 million tonnes we exported in the previous marketing year.

South Africa has already exported about half of the forecast 2.4 million tonnes, and we anticipate more exports in the first quarter of 2026, mainly to the Southern Africa region and the Far East markets.

About 1.4 million tonnes will be white maize and 1 million tonnes yellow maize, for a total of 2.4 million tonnes of exports.

Beyond these export figures, the focus in South Africa is on the 2025-26 production season (which corresponds with the upcoming 2026-27 marketing year). It is still early, and the planting is underway. Excessive rainfall is presenting challenges in some regions, slowing planting and seed germination in areas that have already been planted. Still, there is no panic, and we remain optimistic about the new season’s crop.

Overall, we expect robust maize exports due to a large harvest in the 2024-25 season. The exports will gain momentum in the first quarter of 2024, and Zimbabwe will likely remain a key maize buyer, as it has led imports so far.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Nov 28, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

South Africa’s agricultural exports have remained strong since the start of the year despite significant trade policy shifts and uncertainty.

The cumulative value of agricultural exports for the first three quarters of the year is US$11.7 billion, representing a 10% increase from the corresponding period in 2024.

The exports have been strong every quarter. The latest data for the third quarter shows that South Africa’s agricultural exports totalled US$4.7 billion, up 13% from the same period a year ago. This is due to higher volumes of various product exports and better commodity prices.

The products that dominated the export list in the second quarter of the year were mainly citrus, nuts, apples, pears, maize, wine, sugar, fruit juices, berries, grapes, pineapples, avocados, and soybean, among others.

Although there is still room for improvement in port efficiency, we have witnessed notable gains compared to recent months. We observed a similar experience in the past two quarters. This has supported export activity and illustrates the gains from ongoing policy reforms in South Africa’s network industries.

Regional perspective

From a regional perspective, the African continent maintained the lion’s share of South Africa’s agricultural exports in the third quarter of 2025, accounting for 34% of the total value.

The products leading the export list in Africa were maize, maize meal, apples and pears, wheat, fruit juices, wine, nuts, sugar, vegetable oils, and live animals, among others.

As a collective, Asia and the Middle East were the second-largest agricultural markets, accounting for 25% of total agricultural exports in the third quarter of 2025. Citrus, nuts, apples, pears, wool, sugar, berries, grapes, beef, mutton, maize, apricots, cherries, and peaches accounted for the bulk of exports to Asian and Middle Eastern regions in the third quarter of 2025.

The EU was South Africa’s third-largest agricultural market, accounting for 23% of total exports in the third quarter of this year. The exports to this region primarily included citrus, wine, grapes, nuts, fruit juices, dates, apricots, figs, mangoes, avocados, guavas, apples, pears, berries, and sugar, among other products.

The Americas region accounted for 6% of South Africa’s agricultural exports in the third quarter of the year. The main exported products include citrus, grapes, wine, fruit juices, apples, pears, apricots, and nuts, among others.

Given ongoing concerns about the higher tariffs South Africa faces in the U.S., it is worth highlighting that after some exporters took advantage of the 90-day pause of the higher tariffs and exported more volume than usual during that period in the second quarter of the year, we saw some cooling of exports in the third quarter.

Notably, South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. decreased by 11% in the third quarter of 2025, compared to the same period in 2024, at US$144 million. The composition of the products hasn’t changed much; it is mainly citrus, wine, fruit juices, and nuts, amongst other typical agricultural exports to the U.S.

South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. accounted for a 3% share of overall farm product exports in the third quarter of 2025 (which is part of the 6% exports to the Americas region we mentioned above).

Again, the 3% share of the U.S. in South African agricultural exports is not small, as few specific industries are primarily involved in these exports. These are mainly citrus, grapes, wine, and fruit juices.

Since the start of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), the percentage share of South Africa’s agricultural exports to the U.S. has remained at these levels. From now on, a great deal hinges on whether South Africa succeeds in securing favourable trade terms with the U.S.

It is also worth noting that the U.S. has decided to modify its reciprocal tariffs and exempt certain food products, thereby easing agricultural trade friction, which is costly to both exporting countries and U.S. consumers.

The exempted products include coffee and tea, fruit juices, cocoa, and spices, as well as avocados, bananas, coconuts, guavas, limes, oranges, mangoes, plantains, pineapples, various peppers, tomatoes, beef, and additional fertilisers.

From a South African perspective, it appears that oranges, macadamia nuts and fruit juices will benefit from the exemption.

The rest of the world, including the United Kingdom, accounted for 12% of South African agricultural exports in the third quarter of 2025.

Not a one-way approach

The country also imports various agricultural products. In the third quarter of 2025, South Africa’s agricultural imports totalled US$1.9 billion, a 2% decline year-over-year.

The result is due to slightly lower values and volumes of major products South Africa imports, such as wheat, palm oil, poultry, and whiskies.

Still, the cumulative agricultural imports in the first three quarters of the year are US$5.7 billion, up by 4% from the corresponding period in 2024.

As we have highlighted on various occasions, South Africa lacks favourable climatic conditions for growing rice and palm oil and thus relies on imports of these products. Regarding wheat, South Africa imports nearly half of the annual consumption.

In the Free State province, which was once one of the country’s major wheat-growing regions, production has declined notably over time due to unfavourable weather conditions and the lower profitability of wheat compared to other crops. Meanwhile, imports account for around 20% of the annual domestic poultry consumption.

Consequently, when we account for the exports and imports, South Africa’s agriculture sector recorded a trade surplus of US$2.7 billion in the third quarter of 2025, up 28% from the previous year.

Policy considerations

In the current environment of heightened geoeconomic tensions, South Africa’s export-oriented agricultural sector must maintain its existing export markets and expand into new ones.

The focus for both policymakers and agribusinesses and organised agriculture should be on the following aspects:

First, South Africa should maintain its focus on improving logistical efficiency. This entails investments in port and rail infrastructure, as well as improving roads in farming towns.

Second, South Africa must work diligently to maintain its existing markets in the EU, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas.

Lastly, the South African Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, the Department of International Relations and Cooperation, and the Department of Agriculture should lead the way in expanding exports to current markets and exploring new ones.

South Africa should expand market access to key BRICS countries, including China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. The emphasis should be on lowering import tariffs and addressing artificial phytosanitary barriers that hinder deeper trade within the BRICS grouping. The discussion among BRICS should move beyond the general rhetoric of intent toward meaningful trade arrangements.

There is also a need to increase focus on the broader Asia and Middle East regions, with the same purpose of securing lower tariffs and the removal of phytosanitary barriers.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Nov 20, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

At a time when strengthening ties with other countries is so important, I was happy to see the South Africa–European Union (SA-EU) Bilateral Summit proceed smoothly on October 20, 2025, ahead of the G20 Leaders Summit.

The emphasis was on continuous cooperation, investment and deepening trade. Various agreements and MoUs have been signed, including those on critical minerals and energy. For us in agriculture, deepening relations with the EU is key to our long-term, continuous trade in this fractured world.

While we have had glitches on various occasions on citrus, poultry and beverages, the EU remains one of South African agriculture’s critical trading partners. The SA-EU Summit and the engagement that will follow allow for much greater flexibility to resolve existing challenges and build stronger relations.

I am sounding this upbeat because in 2024, the EU was South Africa’s third-largest agricultural market, accounting for 19% of our US$13.7 billion in exports. Citrus, grapes, wines, dates, avocados, pineapples, fruit juices, apples and pears, berries, apricots and cherries, nuts, and wool were amongst the top agricultural products South Africa exported to the EU.

Now, over the past few weeks and months, some have seen us talk about BRICS, greater Asia, and the Middle East, and have consistently suggested that South Africa should pivot to those regions and deprioritise other traditional and longstanding partners.

But that is not our approach. The approach is to build new friendships and trade relations, while maintaining and nurturing the existing ones. This SA-EU Summit is one such step in cultivating the existing ties.

Remember, South Africa’s agriculture still has significant potential for expansion, with over 2.5 million hectares of land yet to be fully brought into production. When such land is in production, we will require a market for exports, which makes the EU and our efforts in the East so important.

South Africa’s agriculture is export-oriented, and already exports roughly half of what we produce in value terms. Therefore, any increase in production will likely be aimed at exporting to sustain a viable farming economy.

I highlight agriculture here, but the EU is key to many other sectors of our economy.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Nov 17, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

Higher tariffs are a tax on consumers in importing countries. American consumers are experiencing this reality through relatively higher food prices in the country since the Liberation Day tariffs were introduced earlier this year.

Confronted by this reality, the US government has taken steps to modify its reciprocal tariffs and exempt certain food products. This is likely to ease pressure on consumers over time and benefit the exporting countries. South Africa is one of the countries that will benefit from the easing of the US government’s policy step.

Exempted products

The exempted products include coffee and tea, fruit juices, cocoa, and spices, as well as avocados, bananas, coconuts, guavas, limes, oranges, mangoes, plantains, pineapples, various peppers, and tomatoes, as well as beef and additional fertilisers.

The US government’s decision to exempt some food products from these higher Liberation Day tariffs is a recognition of the policy mistake and the unintended consequences of higher prices on households.

South Africa is an exporter of various agricultural products to the US, including citrus, table grapes, macadamia nuts, wine, ostrich products and ice cream.

It appears that oranges, macadamia nuts and fruit juices will benefit from the exemption. This will leave other agricultural industries, such as those producing table grapes, wine, ostrich products and ice cream, still facing higher tariffs.

The US is generally an essential market to South African agriculture, although at a national level, the percentage share seems small. Certain regions of South Africa, such as the Western Cape, have significantly greater exposure.

The US accounts for approximately 4% of South Africa’s agricultural exports, valued at $ 13.7 billion in 2024.

In the second quarter of 2025, South African agricultural exporters took advantage of the temporary tariff pause and front-loaded their products. This resulted in a 26% year-over-year increase in South Africa’s agricultural exports to the US in the second quarter, reaching $ 161 million.

Where to from here?

There remain concerns that the higher tariffs will weigh on agricultural product exports, particularly those not covered in these modified rates, such as table grapes and wine.

South Africa is entering the table grape export season, and access to the US market remains a challenge due to higher tariffs compared to those of South African competitors.

South Africa currently faces a 30% import tariff in the US market. If the country were to be in a position where the African Growth and Opportunity Act, which offers South Africa and other African countries lower duty access into the US, were not renewed, we would face slightly higher tariffs.

South Africa would be likely to face about 33% tariffs if we also account for the previous Most Favoured Nations Tariff rates before the Liberation Day tariffs. These would make access to the US market more challenging for various agricultural products, as competitors such as Chile and Peru face significantly lower tariffs of about 10%, making them more price-competitive than South Africa.

Beyond these modifications, we understand that the South African government continues to negotiate for better tariff access in the US market.

Still, these negotiations, as seen in many countries, are proving to be challenging. For example, the US has imposed significantly higher tariff rates on several countries, including the EU and Japan, which face tariffs of between 15% and 20% even after the “new deals”.

These higher tariffs illustrate that the path ahead will be challenging for South Africa as the country negotiates, still in the process of mending its foreign relations with the US, which typically spreads misinformation about the lies of genocide in South Africa.

For exporting industries in agriculture and specific sectors of the economy, some concerns remain, as the recent modification only benefits a few agricultural industries and does not address the overall exposure of the sector to the US.

Beyond the US, South Africa’s agricultural exports to other parts of the world remain robust. Better access in the US will be an addition to the ambitions of expanding export markets, helping to drive the growth of the sector.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Nov 13, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

We welcome the discussion about the U.S. potentially adjusting the tariffs on foodstuffs. This would be beneficial for U.S. consumers and equally helpful to those in the agriculture, food, and beverage industries that export to the U.S.

While the U.S. accounts for only 4% of South Africa’s agricultural, food, and beverage exports, valued at US$13.7 billion, these exports are concentrated in a few key industries, primarily citrus, macadamia nuts, wine, grapes, and ostrich products, among others.

Therefore, any downward adjustments to import tariffs on these products, especially if they were to apply to all suppliers, would be incredibly beneficial.

South Africa, to an extent, was able to export a decent volume of agricultural, food, and beverage products to the U.S. during the 90-day pause.

Thus, if one considers our agricultural exports to the U.S. in the second quarter, they jumped 26% year-on-year to US$161 million.

It was an ability to utilise the tariff pause period. However, the agricultural products are seasonal, and some, such as table grapes, will only enter the export season in a few weeks and will be unable to benefit from the tariff pause of the past few months.

They face a tariff of 30%, which will weigh on their competitiveness relative to our competitors in Chile, Peru, and others.

Thus, a proposal by Kevin Hassett, chair of the National Economic Council, to discuss lowering import tariffs is a welcome development.

Still, there is no firm commitment, but mainly comments from the economic leaders of the U.S. administration.

Therefore, we will have to watch and see if such revisions occur or if there are any useful developments in this direction.

Importantly, one hopes they can be applied universally so that we all benefit as exporters, and most importantly, for the U.S. consumer to have a variety of high-quality and affordable product choices from suppliers.

Here (linked) is what Hasset said in the Financial Times this morning.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Nov 10, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

South Africa’s agricultural exports have been superb so far in 2025. The large volumes of production for various products, combined with improvements at the ports, have led to encouraging export activity.

For example, after solid export activity in the first quarter of the year, South Africa’s agricultural exports totalled US$3.71 billion in Q2, up 10% from the same period a year ago. This is again a function of both higher volumes of various product exports and better commodity prices.

The products that dominated the exports list in the second quarter of the year were mainly citrus, apples and pears, maize, wine, nuts, fruit juices, dates, pineapples, avocados, grapes, and wool, amongst other products.

While there remains a need for further improvement in port efficiency, significant progress has been made compared to recent years. Agricultural export activity in the second quarter experienced less friction than it had in the recent past.

This encouraging export activity is likely to have continued in the third quarter and the last quarter of this year.

I was reminded of this notable progress yesterday by a note from Dr Boitshoko Ntshabele, CEO of the Citrus Growers’ Association of Southern Africa (CGA).

He stated that:

“In the 2025 export season, Southern African citrus growers packed 203.4 million 15kg cartons for delivery to global markets. This represents a significant 19% increase from the original estimate in April, which was 171.2 million cartons. It represents a 22% increase from the packed-for-export figures in 2024. Driving the growth is a combination of favourable weather conditions in the growing regions and the many young trees that came into fruit this season.”

He further added that:

“Furthermore, unforeseen factors that contributed to the record-breaking performance include the exceptional demand in overseas markets for processing-grade juicing oranges and juicing lemons. Also, the early end to Northern hemisphere supply, which drove strong demand and extended our supply window by adding important sales weeks at the beginning of the South African citrus season.”

I was also encouraged to see the CGA highlighting the improvement in logistics, stating that:

“Improved logistics efficiency, especially port efficiency, was achieved by Transnet, largely through investments in new equipment and the introduction of employee incentives linked to productivity. There was a high level of effective cooperation by all logistics players, including shipping lines, resulting in a productive logistics eco-system.”

In an environment where trade friction and fears of slowing exports persist as a constant concern, such activity is encouraging. We can expect to receive reports of similar activity in other fruits and commodities in the coming months.

However, all this should not divert our attention from the core issue of expanding export markets. We must continue with such efforts.

South Africa’s export-oriented agricultural sector must work to maintain its current export markets and expand into new ones. The focus for both policymakers and agribusinesses and organized agriculture should be on the following aspects:

First, South Africa should maintain its focus on improving logistical efficiency. This entails investments in port and rail infrastructure, as well as improving roads in farming towns.

Second, South Africa must work diligently to maintain its existing markets in the EU, Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas.

Lastly, the South African Department of Trade, Industry and Competition, the Department of International Relations and Cooperation, and the Department of Agriculture should lead the way in expanding exports to current markets and exploring new ones. South Africa should expand market access to key BRICS countries, including China, India, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. The emphasis on the BRICS grouping should be on the need to lower import tariffs and address artificial phytosanitary barriers that hinder deeper trade within this grouping. The discussion in BRICS should move beyond the general rhetoric of intentions to meaningful trade arrangements.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Nov 2, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

On October 21, 2025, on the sidelines of the Financial Times Africa Summit in London, I sat with the CNBC folks for a broad conversation about South African and Southern African agricultural developments and trade.

On trade matters, I highlighted that for its export diversification strategy, South Africa is looking at broadening exports to Asia and the Middle East. The natural and fair question that followed was: What is our strategy for Africa?

The African continent remains vital to South Africa’s agriculture, accounting for roughly half of our annual exports. We exported about $13.7bn (R237bn) to the world market in 2024, and I suspect this year our agricultural exports will cross the $14bn mark for the first time.

Africa has been central to this export growth, particularly the Southern Africa region. Roughly 90c in every dollar of South Africa’s agricultural exports to the African continent are to Southern African countries. These are mainly in the Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Free Trade Area.

We will likely remain heavily dominant in these regions for some time, but the growth is limited. We are not as strong in other parts of the continent.

The product scope of agricultural exports into SACU and SADC is quite diverse. It includes maize, processed food products, apples and pears, sugar, animal feed, prepared or bottled water, fruit juices and wine.

The question is how much more can South Africa export beyond the Sacu/Sadc region, and what is our attitude towards greater Africa?

The most reasonable assumption is for South Africa to target West, East, and North Africa. But such an expansion has limits.

For a start, Africa north of the Sahara, more specifically Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia, is much closer to Europe and its trade activity is more closely linked to the EU than Sub-Saharan Africa.

North Africa, more specifically Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia, is much closer to Europe and its trade activity is more closely linked to the EU than Sub-Saharan Africa. Establishing a market presence in North Africa may prove challenging due to direct competition with well-established EU supply chains and competitive local produce.

South Africa’s realistic opportunity within the African continent is more likely in East and West Africa. Leveraging the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)’s tariff-free movement of goods would potentially boost the country’s agricultural exports to these regions. But, at least in the near term, trade with these regions may not yield many benefits for South Africa.

There are at least three reasons. First, East and West Africa have a range of non-tariff barriers, which could hinder boosting trade regardless of lower tariffs through AfCFTA. Second, high levels of corruption, which increase the costs of doing business, have proven to be a significant concern. Third, fragmented value chains owing to poor connectivity and infrastructure are a major contributor to transport costs.

This narrow scope of expanding agricultural exports in the African continent typically leads to frustration among business leaders, who continue to see improvement in domestic production but are limited in avenues for sales. The major economies in the east and west of the continent, Nigeria and Kenya, remain tiny markets for South Africa’s agricultural exports, each accounting for a mere 2% a year.

Still, Nigeria spends over $6 billion on agricultural imports a year. The key beneficiaries of the Nigerian agriculture market are Brazil, the US, China, Russia, Canada, New Zealand and Germany. This is through imports of wheat, dairy products, sugar, processed food, palm oil and maize, among other products.

Meanwhile, Kenya is a relatively small market with just over $2 billion worth of agriculture and food imports a year. The key suppliers are Indonesia, Malaysia, Argentina, Russia, Pakistan, Uganda, Tanzania, India and Egypt. Kenya’s key agriculture and food imports are palm oil, wheat, rice, sugar, processed food, maize, dairy products, pasta and sorghum.

Therefore, South Africa will play a more maintenance approach rather than hoping for further expansion in the African continent. The near-term growth areas in our assessment are the Middle East and Asian countries. The growing population and better income levels in these regions are among the key indicators.

When South African leaders are in Asia, visiting countries such as Vietnam, China, Malaysia, and India, it is important to consider the implications. Equally, when our leaders are in the Middle East the conversation should focus on export diversification.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

by Wandile Sihlobo | Oct 31, 2025 | Agricultural Trade

American farmers are likely to be somewhat uplifted by the recent US-China meeting. They are feeling the negative impact of the current trade friction, as China has increased its reliance on South and Latin American countries to buy soybeans and other agricultural products.

China is the world’s largest importer of soybeans, accounting for roughly half of global soybean imports. China also imports a range of agricultural products, making it the world’s second-largest agricultural importer. Therefore, a promise from the recent US-China meeting to resume imports of US agricultural products will help alleviate some of the pressures on American farmers.

For us in South Africa, of course, the easing of the trade friction reduces the volatility in the grain markets. However, it doesn’t fundamentally change much of our reality. There are ample grain and oilseed supplies in the world market, which have kept prices generally under pressure. This adds to the fact that South Africa has a large crop.

Therefore, for a South African farmer, there are some financial pressures, particularly if one considers that we will start the 2025-26 planting season with reasonably higher input costs.

For consumers, however, the ample global and domestic grain prices bode well for a continuously moderating food inflation path through 2026.

With all these issues considered, South African farmers remain eager to plant a decent crop area in the 2025-26 season, with an intended area of 4.5 million hectares, up 1% from the 2024-25 season that has just been completed. The weather outlook for the season is broadly positive, suggesting we may have another excellent crop.

Overall, we will closely monitor the issue of US-China grain trade and whether there will be a resumption in US export volumes. Still, even if there is a resumption, China will likely stay on its path to diversify its agricultural product suppliers. The South and Latin American region are the biggest beneficiary of this effort, but China is increasingly looking at other regions, which includes us in South Africa.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)