South Africa has just harvested its largest soybean crop in history

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

We continue to receive encouraging reports on the prospects for La Niña-induced rainfall during the 2025-26 summer season. Most regions of the country have received excellent rain since the start of October. Soil moisture has improved notably across various areas of the country.

The latest forecasts from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University (IRI) indicate a high likelihood of La Niña-induced rains continuing through to February 2026. This period covers the planting through to the flowering of the summer crop, which are stages that require more moisture for development. After the flowering period, warmer, sunnier weather typically helps with crop maturation.

Better rainfall prospects are beneficial not only to field crops but also to the livestock and horticulture subsectors. For the livestock subsector, improvements in the grazing veld, at a time when feed prices are also falling, are a welcome development, as the industry has struggled with financial pressures due to foot-and-mouth disease.

Moreover, the start of vaccination against foot-and-mouth disease on the 12 million head of cattle nationwide (with 7.2 million in commercial herds) suggests the industry may finally be entering a recovery period. Still, it is too early, and the vaccination process will be a major logistical undertaking, in addition to the challenge of securing sufficient vaccines.

Still, the fact that we now have a clearer direction for the country provides some comfort. What will also be vital from now on is the inclusion of domestic private labs in vaccine manufacturing, rather than relying solely on imports and the revival of state-owned institutions.

In the horticulture subsector, rainy weather reduces the irrigation period and helps save on energy costs somewhat. Importantly, having the dam levels recover across the major fruit and vegetable-producing areas helps ensure that, even as we approach the winter season in 2026, field activities will continue normally with better soil moisture and irrigation. These favourable weather conditions have set the country up for excellent fruit and vegetable yields going into 2026.

Still, on the profitability side, a lot will depend on the success of export activity. In 2025, the ports performed better, particularly in the first three quarters of the year, helping to keep exports robust. For example, the cumulative value of agricultural exports for the first three quarters of the year is US$11.7 billion, representing a 10% increase from the corresponding period in 2024.

Although there is still room for improvement in port efficiency, we have witnessed notable gains compared to recent months despite the U.S.’s implementation of tariffs. This has supported export activity and illustrates the gains from ongoing policy reforms in South Africa’s network industries.

Separately, we are now in another busy export period for table grapes, and Transnet’s continued efforts and focus on supporting exports will help ensure we end 2025 on a positive footing and start 2026 on a strong path.

A sharper focus by Transnet is needed even more now, as the Western Cape, a major table grape export port, has recently experienced challenging wind conditions. Therefore, ensuring there is sufficient staff on site to push exports, even in challenging weather, is more crucial. Such effort and focus by Transnet and other logistics organizations will be needed through the stone fruit export season into 2026.

In field crops, planting of grains and oilseeds is underway. The farmers are optimistic and aiming to plant 4.5 million hectares, up 1% from the 2024-25 season. The favourable weather prospects may help ensure that South Africa gets an even bigger harvest than the 20.21 million tonnes in the 2024-25 production season (already up 30% from the previous year).

In essence, the weather outlook remains favourable for South Africa’s agriculture going into the 2025-26 summer season. Interventions through livestock vaccination and a stronger focus on improving port efficiency will help ensure widespread gains in the sector, supporting solid growth in 2026.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

The Business Day has a story today about “Fake honey” detections in some informal, non-franchise outlets of South Africa. This reminded me of the observations I once made back in June 2018.

What follows are observations I made on the 27th of June in 2018, typing a blog from the Pietermaritzburg Airport. Here goes:

A few days ago, I tweeted about honey adulteration, which means producing fake honey with sugar or other ingredients. At the time, I suspected the issue would be linked only to foreign products.

Well, turns out we also have bad guys here in South Africa. How do I know this? From conversations with a couple of beekeepers in Howick, KwaZulu-Natal province.

Today, I went on a honey value-chain outreach program there, and conversations with a couple of beekeepers suggested that adulteration is not only an issue of imported products but has been happening in the country for some time.

Sadly, there is no enforcement, self-regulatory, or ethical trade body to address the issue at the moment — the complaints to regulators have thus far landed on deaf ears.

This, of course, could be confusing for consumers; if the adulterated honey is labelled as “pure honey”, what does a consumer do? (I asked the beekeepers). The best indicator at the moment is “price” — I know this is not the best barometer.

Anyways, on average, a 500-gram bottle of pure South African honey is about R65 or more on the shelf. The adulterated honey often sells at a far lower price than this. In addition, consumers could look to trust larger brands that have a reputation to protect, or to artisanal products where they know the beekeeper.

This pricing issue is not only an indicator for consumers but also has implications for the industry’s sustainability, most importantly for potential new entrants. The pure honey value chain is a bit complex and labour-intensive, which increases input costs.

Then, competition with lower-priced ‘adulterated honey’ would squeeze real beekeepers and also lessen the potential for new entrants.

Honey adulteration could also have health implications, as some consumers favour pure honey for its health benefits.

Enough about my ranting — the key issues that were raised by the beekeepers in Howick today were:

The ‘mixed labelling’ issue on honey products should not be taken lightly, especially given the recent upsurge of ‘natural honey’ imports into South Africa.

South Africa’s honey imports increased from 476 tonnes in 2001 to 4,206 tonnes in 2017.

This is mainly due to steady domestic demand, coupled with a decline in domestic honey production, currently estimated at 2000 tonnes, against consumption of 5,000 tonnes per annum, according to industry experts.

But it is worth noting that, on average, 76% of South Africa’s ‘natural honey’ imports came from China over the past 17 years.

I mention this because the Chinese honey has, in the past, dominated the headlines, but not in a good way. In 2014, food24.com ran an article which highlighted that Chinese farmers were caught producing counterfeit honey.

Europe had similar experiences with imported honey, and the challenge grew to such an extent that in 2014, European lawmakers ranked honey 6th on a list of 10 products most at risk of food fraud.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

The livestock and poultry industries account for nearly half of South Africa’s farming fortunes. So when there are frequent cases of animal disease, there tends to be panic about the impact on growth. In recent years the cattle industry has struggled with foot-and-mouth disease, leading to temporary closures of some key export markets and an increasing financial burden on farmers.

The department of agriculture, in collaboration with organised agriculture, has explored ways to contain the spread of the disease. Still, its ongoing occurrence and severity this year compelled South Africa to adjust its longstanding approach to addressing foot-and-mouth disease and transition to national vaccination. We welcome this decision and believe that if executed well it will help the country control the disease.

South Africa is not the first country to take this path. Argentina and Brazil are among the countries that have opted for vaccination against foot-and-mouth disease in cattle. When any country has managed to control the disease, vaccination typically stops or pauses.

The scale of this work will be challenging, as South Africa has a cattle herd of over 12-million, according to the “Abstract of South African Agricultural Statistics” from the department of agriculture. Co-operation with commercial farmers, agribusinesses, organised agriculture and communities will be vital to ensure the success of the vaccination process.

Significantly, South Africa currently relies on imports of the foot-and-mouth disease vaccine, mainly from Botswana. In this new approach, diversifying import sources to include countries such as Turkey should be a key consideration. The work to revive the Agricultural Research Council (ARC) and Onderstepoort Biological Products (OBP) to produce the essential vaccines domestically is key and must gain momentum.

South Africa must also ensure that other private sector stakeholders are part of vaccine production. Private labs must be included in the vaccination production to diversify the supply and ensure domestic availability in the future.

From a consumer perspective, South Africa’s beef and livestock products are safe to consume.

Moreover, in our view, the start of national cattle vaccination is unlikely to introduce major upside risks to meat price inflation. The vaccination process does not change the path to easing food price inflation in South Africa.

We believe that the vaccination process is likely to be phased, allowing continuous slaughtering at the normal pace. In the medium term, efforts to control the disease also bring some normality to the slaughter process and ease price volatility.

We are highlighting meat because it has been one product in the food basket that has exerted upward price pressure after the announcement of a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in major feedlots led some retailers to panic.

This, however, has now eased, and meat price inflation is slowing, contributing to the general easing of food price inflation in November 2025.South Africa’s consumer food price inflation slowed for the third consecutive month, easing to 3.9% in October, from 4.4% in the previous months.

The primary drivers of the deceleration were mainly fruit and nuts, vegetables, meat, sugar, confectionery and desserts. Ample supplies, combined with the base effects, contribute to the easing of price inflation in these products.

While modestly up from the previous reading, cereal products inflation also remains relatively low on the back of the ample grain harvest. South Africa’s 2024/25 summer grains and oilseed harvest is estimated at 20.08-million tonnes (up 30% year on year). The various fruits and vegetables also delivered ample harvests.

Overall, we remain optimistic that South Africa’s consumer food price inflation will continue to moderate. The benefits of lower grain prices, ample fruit and vegetable supplies and potentially easing meat prices will continue to be the major drivers of the deceleration. We don’t see meat as a significant upside risk on prices.

The challenge of foot-and-mouth disease in South Africa is not over and continues to put pressure on farmers, even as vaccination is under way. Typically, during foot-and-mouth disease outbreaks, the country is temporarily closed to some export markets, leading to a drop in consumer prices.

But this year we saw the opposite. Initially, panic buying driven by retailers’ announcements, rather than a product shortage, was the main driver of meat prices, combined with buoyant consumer demand. We now see an easing of these upward price pressures. As the vaccination process gains momentum in the coming months, we expect to see more normalisation.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

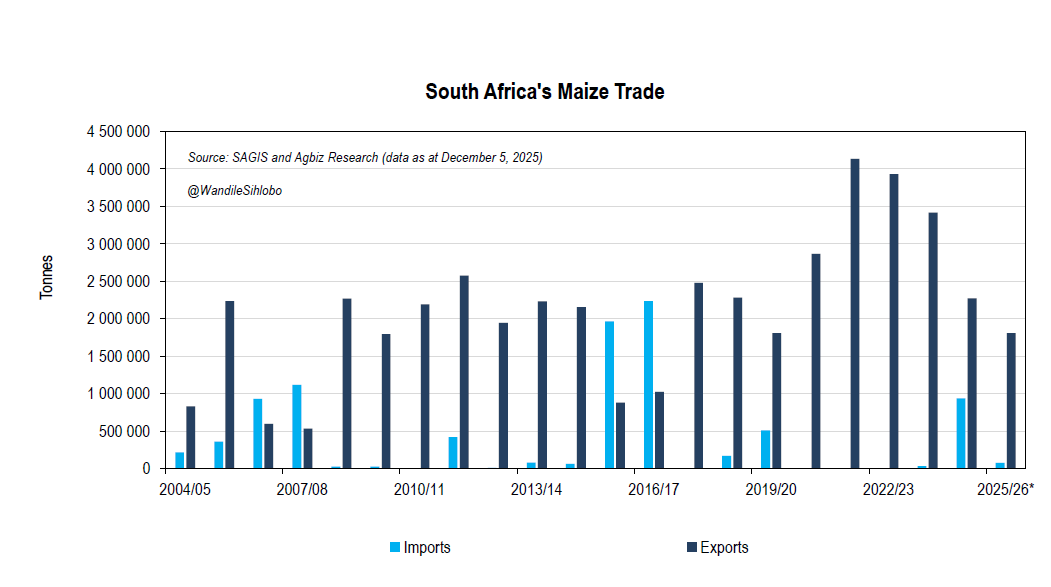

We knew from the start of the 2024-25 season that South Africa would remain a net exporter of maize, as the crop looked promising. With the 2024-25 production season over, with an ample harvest of 16.44 million tonnes, up 28% year-on-year and the second-largest maize crop on record, the export figures are also being revised up.

South Africa will likely export 2.4 million tonnes of maize in the 2025-26 marketing year, which ends in April 2026. This marketing year corresponds with the 2024-25 production season.

This is a slight upward revision from the last export forecast of 2.2 million tonnes. Still, it is down mildly from the 2.8 million tonnes we exported in the previous marketing year.

South Africa has already exported about half of the forecast 2.4 million tonnes, and we anticipate more exports in the first quarter of 2026, mainly to the Southern Africa region and the Far East markets.

About 1.4 million tonnes will be white maize and 1 million tonnes yellow maize, for a total of 2.4 million tonnes of exports.

Beyond these export figures, the focus in South Africa is on the 2025-26 production season (which corresponds with the upcoming 2026-27 marketing year). It is still early, and the planting is underway. Excessive rainfall is presenting challenges in some regions, slowing planting and seed germination in areas that have already been planted. Still, there is no panic, and we remain optimistic about the new season’s crop.

Overall, we expect robust maize exports due to a large harvest in the 2024-25 season. The exports will gain momentum in the first quarter of 2024, and Zimbabwe will likely remain a key maize buyer, as it has led imports so far.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

I’m happy about the warm, sunny weather today and hope for a few more days of it so South African farmers can accelerate fieldwork. Some regions of the country are excessively wet, particularly in KwaZulu-Natal, the Free State, the northern Eastern Cape, and north-eastern Mpumalanga.

We are in the summer grain and oilseeds planting period. The occasional warmer weather helps agriculture by promoting seed germination in areas that have been planted and allowing planting in areas that have not been planted due to excessively wet weather conditions.

Realistically, while not a preference, some regions could still plant through to January. The typical optimal planting period for maize and soybeans is between mid-October and mid-November in the eastern regions of the country. For the western areas, it is between mid-November and December.

Still, we have had many seasons when plantings were more than a month behind this typical window and yet still received excellent harvests. For example, most recently, the 2024-25 production season was roughly a month and a half behind schedule.

Yet, we managed to harvest a record soybean crop of 2.771 million tonnes (up 50% from the previous season) and a second-largest maize crop on record, about 16.44 million tonnes (up 28% from the prior season). We saw an excellent harvest also in other crops.

This ample harvest provides us with confidence that, even if the current 2025-26 production season for summer grain and oilseeds experiences some delays due to wet weather, the country will likely be able to take advantage of frequent warm-weather windows to accelerate plantings.

What we can do at the moment is monitor the weather conditions; nothing to worry about. We have known we would experience a rainy period, as we are in the La Niña weather phenomenon, which typically brings above-normal rainfall across South Africa and the region.

The 2024-25 season of excellent harvest was also a La Niña weather period. Favourable rains supported the agricultural recovery. The gains were across the sector, and not limited to grain and oilseeds. We saw excellent fruit and vegetable harvests, wine production, and grazing veld, all of which benefit livestock.

South African farmers are optimistic; they plan to plant about 4.5 million hectares of summer grain and oilseeds in the 2025-26 season, up by 1% from the previous season.

What we need is more days of warm weather to allow for field work and seed germination.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)

The practices of some countries in the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) are worrying. We continuously see countries restricting imports of agricultural products on short notice, with limited communication to other countries.

Namibia and Botswana are the major culprits of this practice. They blocked South Africa’s vegetable imports in 2021 and at various points in subsequent years.

But in Botswana, when the new President, Duma Boko, came into office, he lifted the bans imposed by the previous administration, as inflationary pressures continued to bite households.

Disappointingly, I learned this morning that the Botswana government is again imposing bans on vegetable imports and forcing consumers to buy local. The Botswana government notice of December 8, 2025, includes a restriction on imports of tomato, potatoes, white cabbage, red cabbage, white onion, red onion, watermelon, green papaya, beetroot, carrot, lettuce, strawberry, ginger, red and yellow peppers, garlic, and butternut.

I sympathise with supporting local farmers and reducing their dependence on South Africa. But I am uneasy with the drastic policy changes, with minimal consideration for regional ambitions.

Among other things, my source of frustration with these restrictions is that these countries are all part of the Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU). This bloc promotes free trade and economic integration.

Nevertheless, the SACU agreement contains a loophole that allows such restrictions. The SACU Agreement states that ‘Article 18 (2) … notes that Member States have the right to impose restrictions on imports or exports for the protection of: health of humans, animals or plants, the environment, treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value, public morals, intellectual property rights, national security and exhaustible natural resources.’

But I don’t see the current Botswana restrictions fitting the above description.

Of course, this action has had a financial impact on South African farmers, who have for many years produced for the domestic market and the region at large. The question that remains is: how should we respond to these events?

South Africa’s response will need to be sensitive but firm. While all this is frustrating, we should not be antagonistic or arrogant, but rather see this through the lens of understanding Botswana’s aspirations, formulate pathways for coexistence, and ensure better communication of policy approaches within the region.

Having hostile neighbours will not benefit any of these countries’ citizens. After all, people primarily want affordable, accessible and safe food. Botswana could therefore close the market in specific windows to boost domestic production and should clearly communicate this to South Africa. The South African producers would then fill specific windows when gaps occur in these markets.

For long-term planning, it would also help if these countries communicated to South Africa which agricultural products they deem ‘national security or sensitive’ and which they want to boost their domestic production of over the years.

This would help better plan the agricultural export drive to other regions and progressively reduce dependence on its neighbours. Importantly, these import bans should not be perpetual but have time limits once Botswana’s producers have restarted their industries and can compete in open markets with South Africa.

The growth or desire to expand agricultural production in these countries also has a positive spillover effect on South African agribusiness, which can supply farm implements and inputs to them. Botswana should remain open and not hostile in this respect.

These Southern African countries should revive the regional spirit and formulate agricultural policies and programmes from that perspective.

I must also state that South Africa has benefited significantly from exports to the African continent. For example, in the record agricultural exports of US$13.7 billion in 2024, the African continent accounted for roughly 40% of the destinations. This figure has been the same for the past decade.

Importantly, for every dollar of agricultural products South Africa exports to the African continent, 90 cents are traded within the Southern African region. Thus, an engagement with this region on the export ban must recognise that South Africa, as a country, depends heavily on the Southern Africa region.

In essence, we must ensure that SACU works for all and that South African industries don’t become disadvantaged by poor policy communication in the region. Overall, as these issues continue, there is value in reviewing SACU and its benefits for all members. This review is now also about broader trade policy, as South Africa seeks to expand its export markets and is often hindered by SACUS-related issues. But I will have a lot to say about that someday.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my newsletter here for free. You can also follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo)